The King's English

Bible Translations Reconsidered

This past year, Crossway, the publishing company which manages the English Standard Version (ESV) of the Holy Bible, announced a minor textual update to the ESV. This set off a minor firestorm in the online Bible world. In reality, only a few verses had any changes. The most impactful change in the 2025 text was to reverse a major change made in the 2016 ESV revision: the translation of Genesis 3:16. For the record, this was a great decision. The update begs the question, though: if such a minor change is bordering on a scandal, is there something deeper at play when we change the way the Bible is translated?

I am convinced there is. I believe we, as a Christian culture, must seek the ideal of a standard Bible. By this, I mean we need a shared DNA across Christian divisions and denominations that echoes the centuries of God’s Word coming off the lips of English-speaking peoples. We had this in the English-speaking world for centuries. The norm persevered until the 1970s, when the New International Version (NIV) was released and instantly became the second most popular Bible translation ever, only second to the King James Version (KJV). The NIV, for all its good, simply does not sound like the Bible in English in many instances.

In truth, I think any Bible that adheres to the English Bible tradition, and finds continuity with it, can be a standard Bible, as I’ll explain below. For example, If you are reading the NKJV every day and I’m reading the ESV, we are largely going to be on the same page about how Scripture sounds. I believe that is at the heart of why it is such a scandal of the mind when a standard Bible in the English Bible tradition has a textual update, like the ESV’s recent one. The fewer updates, the more spread out they are, the better. In recent decades, publishers have been too quick to issue updates.

Let me be clear about what I’m saying. I am not saying you shouldn’t read translations like the NIV. I am not saying these translations are bad. What I am suggesting is that when we make them our primary, or standard Bible (used in church readings, liturgy, families, and such) they erode the identity of how the Bible sounds. A standard is deviated from. Allow me to explain why that standard is so important in outlining my four criteria for selecting a standard Bible.

It must be translated in the English Bible tradition.

It must have the Apocrypha translated.

It must be widely available and accessible.

It must rightly handle textual criticism.

My Criteria for a Standard Bible

1. It must be translated in the English Bible tradition.

As I have argued elsewhere, in the English-speaking world we have a cultural memory of Scripture. The importance of this cannot be understated, and preserving the cultural memory is decidedly important. The words of Scripture being on the lips of believers and nonbelievers alike is a ministry of the Holy Spirit, and I fully believe He uses cultural memory to draw people to Himself, to instruct, and to admonish. Untold hours of blood, sweat, and tears have gone into establishing this cultural memory, and it must be preserved because it is a net societal good for the truth, beauty, and goodness of Scripture to be present in our culture. This has established a pedigree, an aphoristic quality, meaning there are certain words and phrases that sound ‘right’ when said in English, and evoke the brilliance of the language.

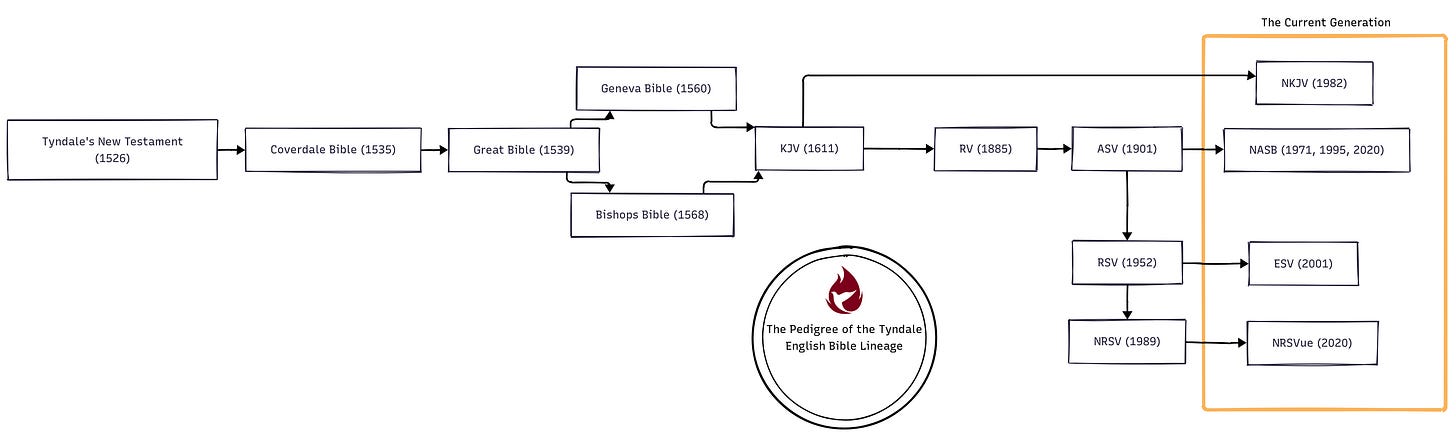

Of course, I greatly value translations that are outside the English Bible tradition—especially the CSB and the NET. I find them refreshing and good tools for study alongside the original languages. Yet, they can’t replace our cultural memory for a variety of reasons. Chief among them is our cultural memory grounded in the Tyndale-King James lineage. In the English world, before the publishing of the NIV in 1978, nearly every Bible was in this lineage: from Tyndale’s New Testament in 1525 to the Revised Standard Version in 1952, everyone was reading from Bibles of the same lineage and a shared base text. That means for over 450 years, the culture of the English-speaking world was influenced by one shared biblical basis, with only minor variations, but largely grounded in the stability of the King James Version (KJV) and those translations derived from her. It is impossible for a new Bible tradition to have that level of impact. New translations only divide the English pedigree, and the rise of new translations have not created new pedigrees. Rather, there is the traditional pedigree on one hand, and disarray on the other.

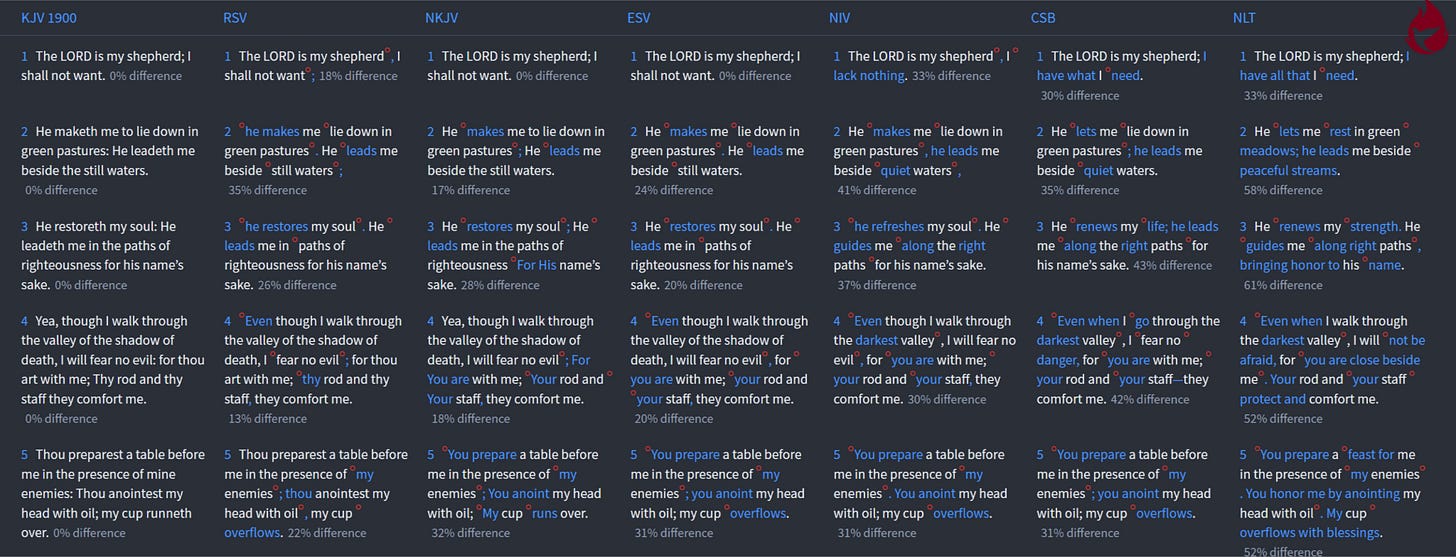

The CSB’s translation of Psalm 23:, which reads, “The Lord is my shepherd; I have what I need,” will never be ingrained in our imaginations like “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want” (KJV, RSV, NKJV, ESV, NRSV, etc.). The main differences of Psalm 23 in the Tyndale-derived translations are in punctuation, grammar, and pronouns, while the new translations introduce completely new English phrases and words in translation. These translations are not inaccurate to be doing so, but they are eroding the cultural memory, or at least not supporting it, hence why they do not qualify as a standard Bible in my criteria.

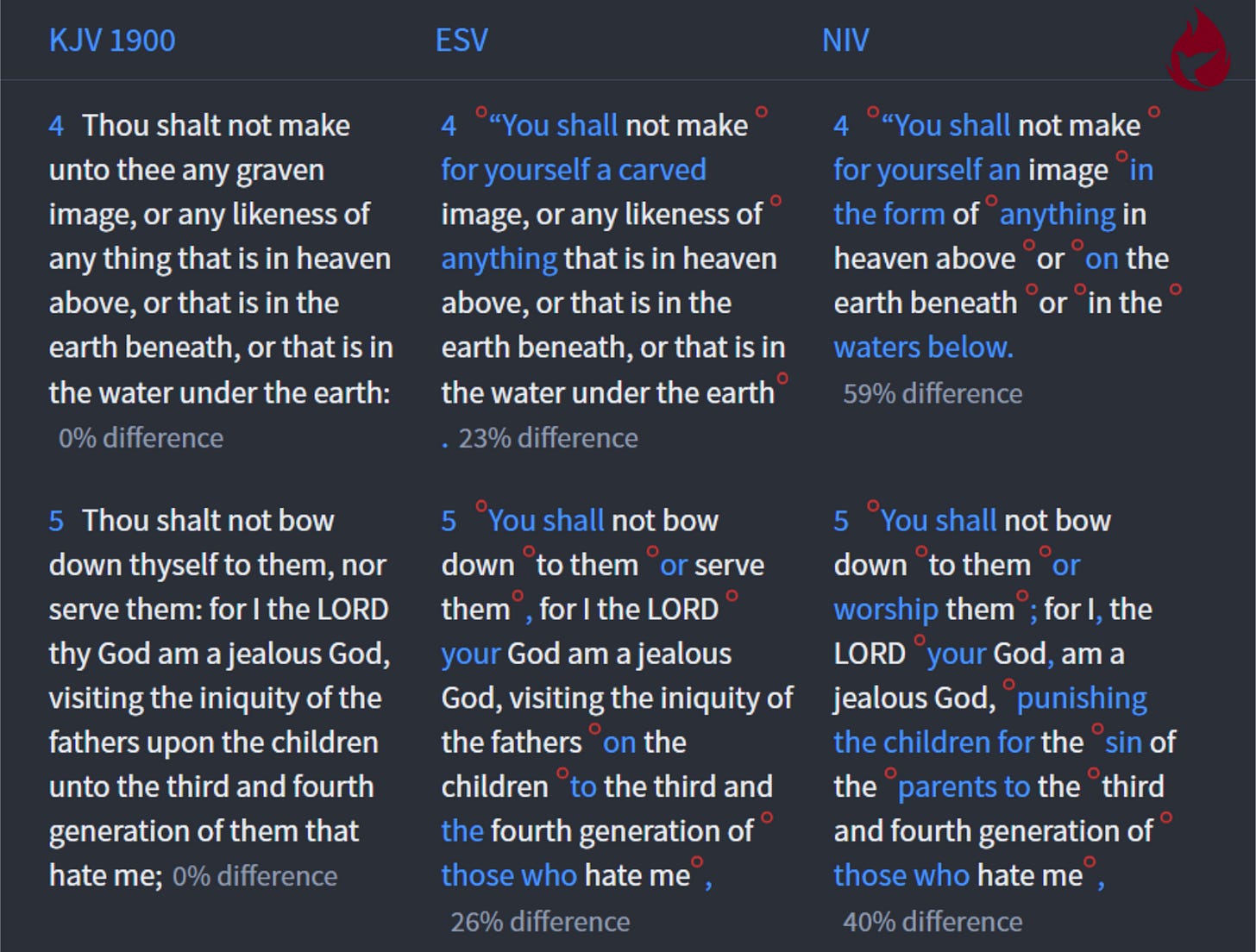

There is a liturgical and catechetical component to this argument that must be clearly stated. As the Scriptures are read within the congregation and over family dinner tables, they are being etched into the fabric of the family, congregation, community, and culture. Therefore, the translation being read from in worship settings ought to support the cultural fabric of the community and culture, not erode it. For example, if a family is teaching their children The Ten Commandments, or perhaps some of the family learned them in Sunday School growing up, they may be able to find themselves reciting nearly word-for-word as it is being read in the ESV. It is likely the older folks in the pews grew up on the KJV, RSV, or NKJV and taught their children and Sunday School classes from it. Yet, consider the mental gymnastics parishioners will undergo if the Bible is being read in the NIV:

Hopefully an example from my own life will make this more clear: I was not raised to read the Bible or memorize Scripture. The one exception to this occurred when my father sat me down and we memorized Psalm 23 together from a tiny red Gideon KJV. Aside from that, I should have come to the faith not really knowing any Bible. Yet, when I began attending a church, it was a UMC that used the NRSV, a Bible in the cultural lineage, and I found myself surprisingly being able to mouth some of the readings as they were happening. God blessed me and used the cultural memory of Scripture to give me grace, and I did not even know it! Later, when I was attending a church that mainly used the NIV, I found myself experiencing hearing the Word read as a roadblock. The reading of the translation in the midst of the congregation was warring against this special grace of cultural memory, eroding it, not supporting it. If this is the case for someone raised with little-to-no Bible like me, how much more profound is it for those who have more?

A consistent problem with modern translations unhinged from the Tyndale-King James tradition is they explicitly translate words so they do not sound like the Bible. This is stated in the prefaces of many of these translations. This is assumed to be an advantage, a good thing. Why? While it can be a good thing to explore the lexical possibilities of a word, it is not a good thing to purposely de-theologize it. Leland Ryken reports that, when discussing the translation of ἱλασμός (propitiation), a member of the NIV committee said, “Propitiation is exactly the right word, but we cannot use it because people do not know what it means.”1 This gets at the root of the issue: is the Bible meant to communicate to us, speak into our culture, lives, and hearts the Word of God? Or is it to fit the Word of God into the present vocabulary of our cultural moment? Certainly, there is a case to be made that simpler vocabulary-based translations have uses for evangelism and other use cases, but we seem to be choosing to degrade our theological vocabulary rather than maintain it when we purposely choose such translations as our standard Bibles.

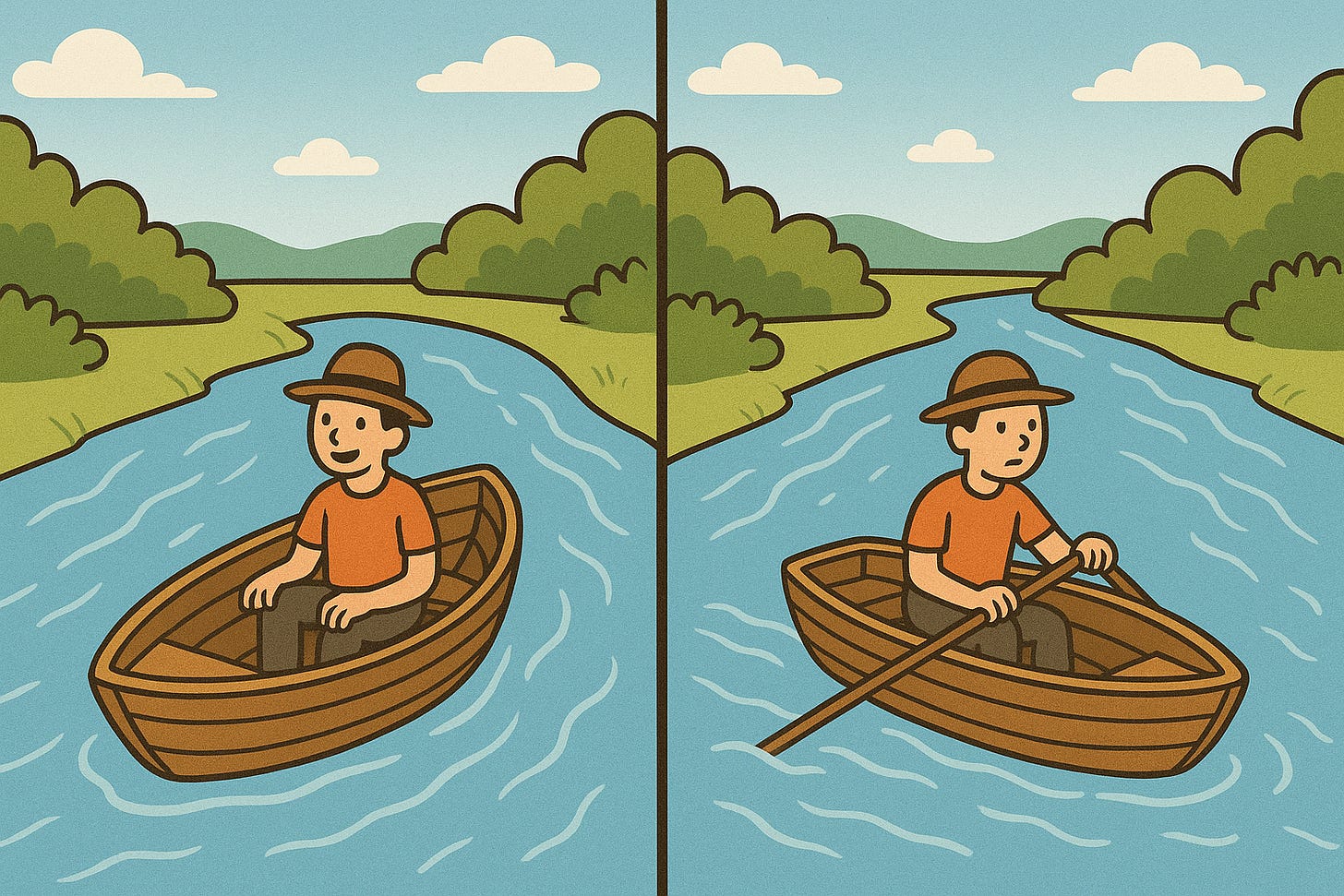

I want to be clear: no matter what translation is used, the reading of God’s Word in the congregation is a means of grace, whether the NIV or KJV or whatever. My point is we can be inhibiting another, secondary, function of that grace when we ignore that we are warring against the cultural memory of Scripture, knowingly or not. It is the difference between flowing with the stream and letting it carry us, or putting an oar in the water, dragging it on the surface, and thereby fighting the current.

2. It must have the Apocrypha translated.

Few modern Bibles, especially those Bible translations initiated by Protestant bodies, have the Apocrypha translated. Elsewhere, I have argued why the Apocrypha needs to be maintained, read devotionally, and used liturgically in churches. In summary: it is ours, part of our religion, we dare not forsake it any more than we forsake Lewis’ Mere Christianity or the works of the Apostolic Fathers, even if it is not inspired Scripture. In fact, we have a higher duty to preserve and read it than Mere Christianity. Therefore, it is my second criteria for a standard Bible.

The glaring omission of the Apocrypha stands out most in the New King James Version (NKJV). For all intents and purposes, the NKJV should be the Bible I am using. It does everything I am looking for in points 1, 3, and 4 much better than the others. It is more readable and does a slightly better job at preserving the English Bible’s cultural memory. Yet, its origins from mostly conservative Baptists and Presbyterians left the Apocrypha on the cutting room floor, despite it being an integral part of the KJV. This exclusion is a hinderance to the NKJVs claim of being a direct successor to the KJV.2 The other major translations claiming continuity with the KJV—the RSV and its successors the ESV and NRSV—do include the Apocrypha. This is to their credit. Hopefully, translating the Apocrypha in the future is not outside the realm of possibility for the NKJV.

There is a factor of this that comes down to tradition: I am an Anglican and keep the Daily Office. Several times a year, we read from the Apocryphal writings both in the Daily Office and in Sunday worship. If this is not your tradition, it may seem less important. Whether this is your practice or not, however, I would still argue the availability of the Apocrypha is an essential component of what constitutes a standard Bible, as was the case until the late 1800s. I would also argue it is our duty as Christians to reclaim the significance of these writings as they are losing status.

3. It must be widely available and accessible.

It is important for a standard Bible to be readily available and accessible for obvious reasons: people have to be able to read it! It shouldn’t be hard for me to buy my children or friends Bibles in our family or parish’s standard Bible. When it comes to translations that meet criteria one and two, only a few translations remain: the RSV, NRSV, NRSVue, ESV, and the venerable KJV. Accessibility and availability narrow it down even further.

“Thy word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path.”

- Psalm 119:105 (RSV)

The Revised Standard Version (RSV), the predecessor and “father” of the ESV, has become my favorite Bible translation. In many places, it tastefully preserves the traditional second-person pronouns for God (thy/thou/thee/thine), which you can see in the example above. However, it lacks the ESV’s incredible lineup of availability and digital accessibility. The RSV is only available in print in one edition by Thomas Nelson, aside from a few Roman Catholic publishers who publish a niche revision which removes the thees and thous, defeating the advantage. This is in large part because the RSV was abandoned by its translator and license holder, the National Council of Churches, who produced and published the NRSV (and have pulled and abandoned that Bible, too) and currently only publish the recent NRSVue. Of course, used copies of the RSV are available in plenty, but it is a barrier-to-entry that the RSV is still widely unavailable today. While Crossway ever increases their publishing of beautiful ESV editions and has the bestselling study Bible ever, the RSV tragically barely hangs on to being in print.

It is unfortunate that market share has such a big impact, but it is the reality of the world we live in. Behind “market share” is consumer enthusiasm: enthusiasm drives publishing. If a Bible will sell, it will be produced. The enthusiasm behind the ESV is such that it is the most widely available and accessible translation today. Aside from print, the ESV app is easy-to-use, intuitive, and offers access to the whole lineup of Crossway’s study Bibles and other resources. While the RSV is available on the YouVersion Bible App, there is not much offering past that (and there are serious concerns about the YouVersion app being susceptible to drift).3 The ESV is wiping the floor with the competition in availability and accessibility, and there are multiple editions in print with the Apocrypha included. So, unfortunately, the RSV and original NRSV do not meet this criteria.

And then there were three: the NRSVue, KJV, and ESV.

4. It must rightly handle textual criticism.

There is a part of me that would like to discard textual criticism entirely and just use the King James! However, the insights of textual criticism, when rightly used, are indispensable. Take, for instance, the impact the Dead Sea Scrolls have had on our ability to rightly translate the Bible. Yet, textual criticism must not go as far as to destroy the text it is criticizing.

The New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition Does Not Meet This Criteria

The glaring example of textual criticism killing a good thing is the unfortunate case of the NRSV, Updated Edition (NRSVue), which is a recent revision of the NRSV, a 1989 update to the RSV. With the release of the NRSVue, it was announced the original NRSV, which for decades has been the standard in academica, would sadly be pulled from print and, unlike the RSV, all digital platforms as well.

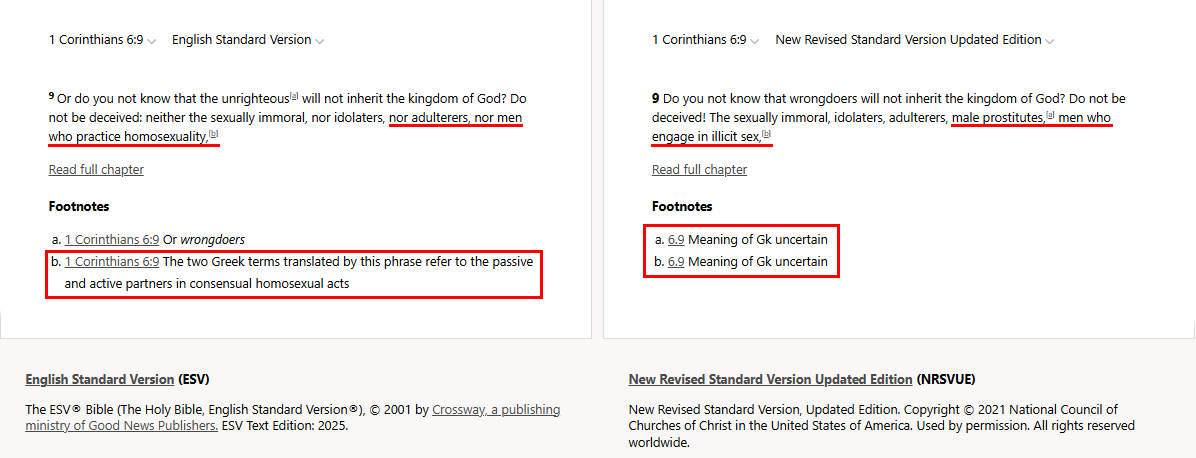

Unfortunately, the NRSV’s successor, the NRSVue, took significant revisionist liberties with the biblical text that do not reflect accurate translation, opting for liberalism and mistranslating the sacred words of Scripture. In the most egregious instance, they devilishly affirm modern anthropology and sexual confusion as they translate 1 Corinthians 6:9 in this way: μοιχός (adulterer) as “male prostitute” and ἀρσενοκοίτης (homosexual) as “men who engage in illicit sex.” They comment on the translation with the same footnote on both: “meaning of Gk uncertain.” The truth here is the Greek is only uncertain to someone who fell asleep in their first-year Greek class or is just dishonest and is trying to rewrite Scripture to fit their agenda.4 In contrast, the ESV footnote of the same pericope conveys important context known to scholars. What gives? Has scholarly understanding changed? No, the NRSVue is actually just choosing to completely ignore all scholarship and do what they want.

This mistake is so egregious that the publishers have recently issued a slight change, an errata, changing the footnote on the passage to “Meaning of Gk uncertain, possibly men who have sex with men.”5 The errata matters little: the damage is done, and their hand is displayed: thousands of these Bibles have been printed and adding the accurate reading in the footnote as a possible reading does little to rectify the violence done to the text. As of today, the online edition of the NRSVue on BibleGateway does not even reflect the errata, as my screenshot demonstrates. They are altering their translation of the Word of God to fit Western postmodern cultural norms. The same ones who decry colonialism are committing colonialism of the text, imposing their modern Western views of sexual ethics. It is truly unfortunate because some great scholars worked on certain books in the NRSVue like Brent Strawn (Exodus) and David A. DeSilva (4 Maccabees). Yet, the whole project is tainted by those who made the egregious changes, the responsibility of which ultimately falls on the shoulders of the general editors who let this atrocity make it to press and whose hands may have tainted any part of the translation yet to be discovered.

Majorly disappointing is that the Roman Catholic Church has granted the NRSVue an imprimatur, official permission to be used, with zero changes. This is without precedence as the RCC required changes in the RSV, NRSV, and ESV, resulting in the RSV-CE, NRSV-CE, and ESV-CE, “Catholic Editions” which have minor changes to reflect Catholic theology—usually minor conservative changes. Apparently, the NRSVue’s theology of sex and gender do not require changes to conform to Catholic teaching, according to the RCC’s decision. This is beyond disappointing.

Needless to say, the NRSVue is not an option that meets my criteria because of how fast and loose it plays with the text, imposing a heterodox agenda and anthropology.

The King James Version Does Not Meet This Criteria

This fourth criteria will be where the King James Version runs into trouble, too. The King James is a fine Bible. If Tyndale and Coverdale are the roots of the tree of the English Bible tradition, the KJV is the trunk—the bulwark. For centuries, it has done the heavy lifting. Yet it can’t be ignored that there are two factors which negatively impact the use of the KJV in the 21st century.

Archaic Language, But Not What You Think

Firstly, there has been change in the English language since 1769 (the year of the final KJV revision and what we all read today when we read the KJV). Now, I am not talking about second-person pronouns. As with the RSV, they are perfectly acceptable and I do not believe them to be a barrier. In fact, I believe the traditional pronouns amplify our speech and understanding of God. By archaic, I mean the instances in the KJV where the word used in translation has completely changed meaning. For example, Psalm 5:6 (KJV) says, “Thou shalt destroy them that speak leasing…” In the 1600s and 1700s, to lease meant to lie, to be in falsehood, to deceive. Today, leasing is a contractual relationship. A “modern” translation of the verse: “Thou destroyest those who speak lies” (RSV). There are numerous examples like this that actually inhibit our understanding of God’s Word, which is the opposite goal of a translation, which is to make the Bible understandable in our language. It seems reasonable that every 300-400 years, a few words will have reached such a point.

The Dreaded Manuscript Conversation

Secondly, the manuscript corpus is very different today than in the 1600s. This is not a topic which is easily addressed, so please bear with me or ignore this entirely, which is acceptable.

To avoid unnecessary trifling, I will focus on the New Testament. The KJV was translated with Erasmus’ Greek manuscripts corpus as the primary source. One of Erasmus’ emphases was an early form of text criticism, and along with that, he sought to compile the best manuscripts he could at the time. He was also a frequent visitor to England and friend of Sir Thomas More. Tyndale, Coverdale, and the other English translators relied on his compilation to do their own work. The Reformation owes a lot to Erasmus! His manuscript tradition is called the Textus Receptus (TR). However, our manuscript corpus has increased dramatically since the early 1500s. We have what scholars believe are vastly more ancient and more precise manuscripts. None of them change any doctrine from what the King James translators were working with, but with more evidence we can be simply more precise in grammar, identify scribal errors, and lessen the effects of transmission.

For example, where Erasmus found gaps or his manuscripts were damaged, he had to reverse translate from the Latin Vulgate to Greek to complete them. We do not have the same problem with the Critical Text (CT), which is the main manuscript collection modern Bibles are translated by. They are complete and composed of very early manuscripts and manuscript fragments. Scholars are able to note all sorts of divergences that can be traced down to the source. For example, if a scribe in 218AD added a footnote, and his manuscript was copied in 220AD, his copier may have accidentally added that footnote to the body of the text. Then any copies of the copy have that addition. Afterward, this is confirmed with manuscripts that match the earlier one from a different time or place. Biblical scholars have largely tracked down these small discrepancies. It is important to again emphasize: none of these small discrepancies change Christian doctrine.

One of the clearest examples of this divergence is the Comma Johanneum, or John’s short clause. 1 John 5:7 (KJV) reads, “For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one.” The first two editions of Erasmus’ manuscripts actually did not have the Comma Johanneum because he could not find a Greek manuscript with it included (though it is in the Latin). However, a single undated Greek manuscript was discovered in-between his editions with it present, and he decided to include it. Thus, it made it into the KJV. The Comma does not appear in modern Bibles because the manuscript evidence shows it is a marginal note. Clement, writing in the 200s, quotes 1 John 5 in his writings and his quotation is missing the Comma as do nearly all Greek manuscripts, as Erasmus’ earlier editions indicated. This is just one example, and is perhaps the most well-known and one of the largest manuscript divergences.6

A larger example is the tale of the woman caught in adultery (John 7:53-8:11). I commend my friend Jonathan Arnold’s article on HolyJoys to you for a proper walkthrough of that passage.

Now, it is true that the NKJV, in keeping with its claim of merely being an update of the KJV, is still based on the TR manuscript tradition. However, one thing it does that no other Bible does (but probably should), is have extensive footnotes about manuscript differentiation—thereby preserving the English Bible cultural memory, while incorporating the latest scholarship from the CT. It was a genius way to go about the NKJV as a project, and I would happily have this as a feature in any Bible. Unfortunately, the King James Version we all have ready access to today, the 1769 text, does not, and, along with the archaic words, means it does not meet my four criteria.

Final Thoughts

I hope in sharing my four criteria for what should make a standard Bible standard you are encouraged to think through the larger impact of choosing a Bible translation for your churches and families. It is not an insignificant thing. On the release of the New English Bible in 1962, T.S. Eliot remarked, “We ask in alarm: ‘What is happening to the English language?’” We are part of answering that question in the Bibles we choose to read.

These thoughts have led me to primarily use the English Standard Version (ESV) and the Revised Standard Version (RSV) in the majority of use cases in my life and as my family reads Scripture together. This is reinforced on Sundays as our Anglican parish reads Scripture from the ESV. Though I often compare translations when exegeting a passage or preparing a sermon, I find few use cases to read outside the deeply rooted English Bible tradition anymore.

Ryken, The ESV and the English Bible Legacy, p. 163-164

Notably, the NKJV does not claim to be a new translation, but rather the fifth major revision of the King James Version. See their claim here.

YouVersion has a complicated history and continues to platform heretical translations like the Passion Translation. Recently, their algorithm seems to be favoring certain theological perspectives. (For example here.)

Biblical scholar Mark Ward has some great work on this subject. This paper he presented is of particular value for understanding the minds of liberal biblical scholarship.

The website KJV Parallel Bible is a great resource for comparing the TR and CT side by side. The differences are truly minute.

Well, you've convinced me - I think I'll revisit the RSV for my February Psalter devotion. I usually cycle through ESV, HTM, and (New) Coverdale (1662/1928/2019, depending), but periodically pull KJV, NRSV, or NIV(84) just for a fresh sound.

Thanks for this, and the Defense of ESV article.

Perhaps, the Wild-West-approach to English translations reflects the cultural approach to Scripture in the Protestant and non-denom world: The Bible is primarily seen as a document for personal study/me-and-Jesus American spirituality, rather than as a document for the corporate, liturgical body. Your article names for me what I've really struggled with when it comes to memorizing Scripture. Which translation should I memorize? I don't want to memorize a translation that's unrecognizable or clunky to others. When I officiate at funerals, one of the more powerful experiences is when I recite the KJV translation of Psalm 23 and others join from memory. Thus, my previous question about the Coverdale: Should I memorize psalms out of the Coverdale, the KJV, or what?