Duality of Purpose

The Case for Using (At Least) Two Bible Translations

Over the past few years, I have been, at times, a bit snobbish when it comes to Bible translations. For that reason, I think it is necessary to briefly explain where I’ve come from. Over the past decade of being a Christian I have answered the question “Which [one] Bible translation should I use?” several different ways. I’ve always been searching for “the one.” Over time, which one is “the one” has changed several times. Now that we’re moving into a new year I have yet again come to a new conclusion, but this time things are different for me.

I do want to add a disclaimer. The correct answer to “Which Bible translation should you use?” is ALWAYS “The one you’ll read.” I’m going to propose reading two Bible translations in English, but the caveat is the goal can be a distraction. Even if you don’t find my argument convincing, the most important thing is that you are reading Scripture daily. As N.T. Wright says, “If you’re not reading Scripture day by day by day you’re implicitly reading other things which are taking its place.”

Now, back to my epiphany about Bible translations and why I believe I’ve finally got it right and found a system that works after all these years. Warning: I’m going to be dropping a lot of acronyms in the following narrative. If you don’t know what they are, that’s okay, my hope is everything will make sense by the end.

Where I Started With Bibles

When I first began researching Christianity, before I even converted, I went and bought two Bibles: an NIV made of recycled paper and a KJV. I believe my reasoning was I wanted something new and something old. Truthfully, though, I struggled to enjoy the KJV and the NIV became “my Bible.” That was until I joined a church and, upon graduating high school, I was given a copy of a niche translation called the CEB by the church as a graduation present. I had never been given a Bible before and boy did I LOVE that thing, not because I felt any way about the translation, but because it was given to me. I used it exclusively until my sophomore or junior year of college. In the circles I was running in during college the ESV was the top dog and I ended up making the switch and using it until seminary.

I took a gap year between college and seminary and I found myself experimenting more. I returned to the NIV and found it a refreshing change of pace after a few years of ESV-exclusivity. Anticipating engaging in more academic circles, I also started reading the NRSV (the ESV’s slightly older cousin). After a while of going back and forth and eventually getting frustrated with the back and forth, I just settled on the NRSV and endeavored to make it my Bible throughout seminary. That was my plan until 2021 and I started dabbling in the CSB, the Christian Standard Bible (not to be confused with the earlier referenced CEB). After reading it a bit I found it the most refreshing and readable yet accurate translation I have experienced yet. I read through the Bible in a Year with it in 2022 and took a critical look at it as I began to study Greek. I thought I’d found a new “one.”

The Misconception I Adopted

I began using the CSB in 2022 as my exclusive Bible for four reasons: 1) in my opinion it reads incredibly well in modern English, better than any other translation, 2) it has great prose and poetry compared to most other English translations, 3) it tends to strike the balance on the issue of gendered language very well, and 4) it is a “fresh” translation, not in the lineage of the Tyndale-King James tradition. What does that mean? I’ll get to that soon, first I feel the need to address the misconceptions I had, misconceptions I believe are shared by us all.

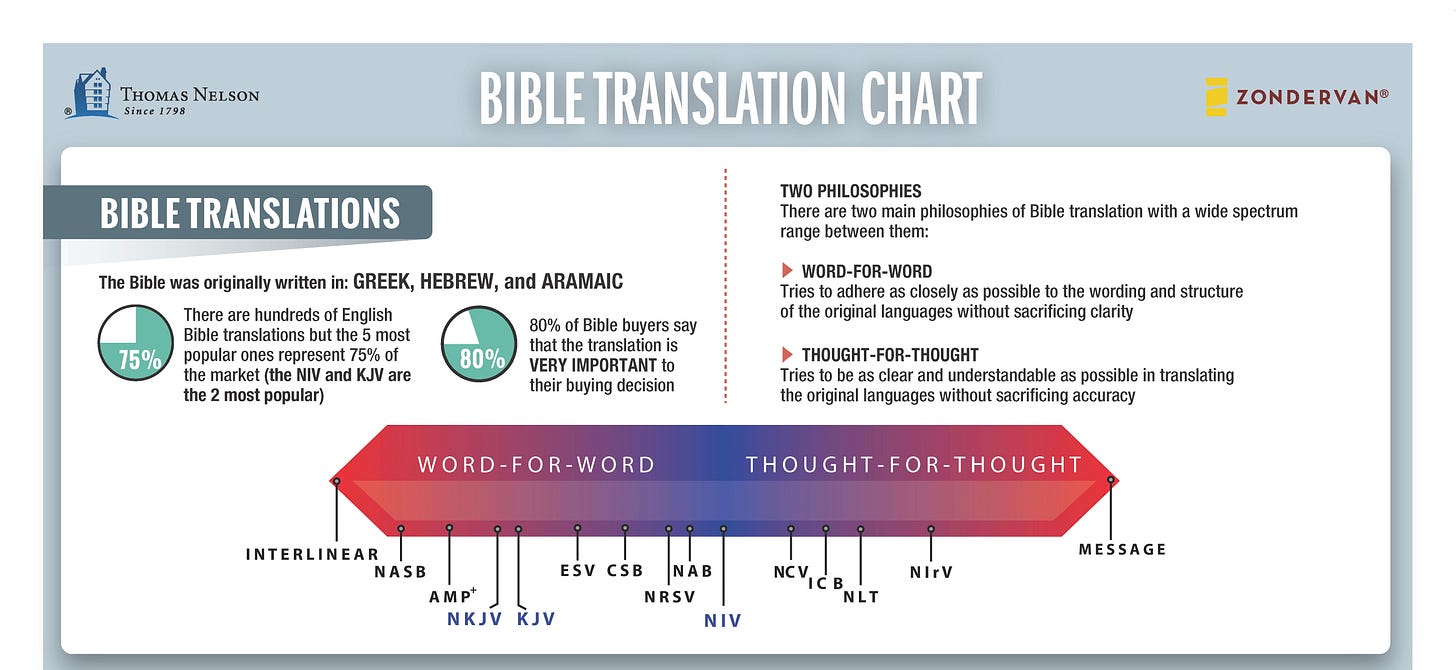

Everywhere on the internet there are “Bible translation charts.” Usually they’ll have an axis, with “word-for-word/more literal/formal equivalence” on one end and “thought-for-thought/less literal/dynamic equivalence” on the other end. Here’s an example of a popular chart produced by HarperCollins, a large publishing company that owns Bible publishers Zondervan (NIV) and Thomas Nelson (NKJV):

Over the past year, I have found a severe category error in how these “translation charts” market Bible translations. The axis is simply wrong. When a Bible translation is commissioned the publisher or translation committee casts a vision for the translation. Usually, they see some unmet need in the world of Bible translations and seek to meet it. You can read their justifications in the front of your Bibles in the preface to the translation. All of the translations, however, in some way seek to find the right balance. This is the true goal of all English Bible translations: to faithfully render the original languages into English.

Truthfully, there are no word-for-word translations on one end and thought-for-thought on the other end. All have instances of what can be called word-for-word and thought-for-thought translations. Let me give an example of what I mean.

A literal translation of John 3:16 might read like this:

“in this the way for loved the god the world so that the son the only he gave in order that each the believing into him not perish but have life eternal”

Even that literal example wasn’t a “word for word” translation because of cases like the first word, οὕτως, the example uses multiple English words (“in this the way”) to begin to properly translate one Greek word. Alternatively, you can go the route of other translations and translate the phrase οὕτως γὰρ as simply “for [God] so loved,” changing the sentence structure a little and moving “God” in between the adverb and conjunction. See where I’m going? Neither of these routes are “word-for-word” or strictly “literal,” and every phrase in the Bible requires translators to evaluate and decide how to best render it in English just like this example. Taking the chart above as an example, even the Bible they claim is farthest in the word-for-word camp, the NASB, is truly miles and miles from an interlinear, which is a bible that imposes an English gloss and a biblical language side-by-side.

That’s not to say there aren’t categories, indeed there are. The NASB and NLT for example are categorically different, you can tell by simply reading them side by side. Bill Mounce, a preeminent Greek scholar who serves on the translation committee of both the ESV and NIV, argues there are actually five categories, only three of which meet the criteria of true English translations. He makes a good case for these categories and I believe he is right, but that isn't my focus in this article. (His article can be found here if you want to know more.) I would like to share what I’ve found over the last year.

You Need (At Least) Two Bible Translations

After spending a year in the CSB, half a year studying Greek, and then reevaluating everything I have learned and know up to this point I’ve come to this conclusion: you should be reading from at least two Bible translations:

A Bible translation in the lineage of the great English Bible tradition (called the Tyndale-King James lineage)

A “fresh” Bible translation that is translated without the Tyndale-King James lineage in mind

The Tyndale-King James Lineage

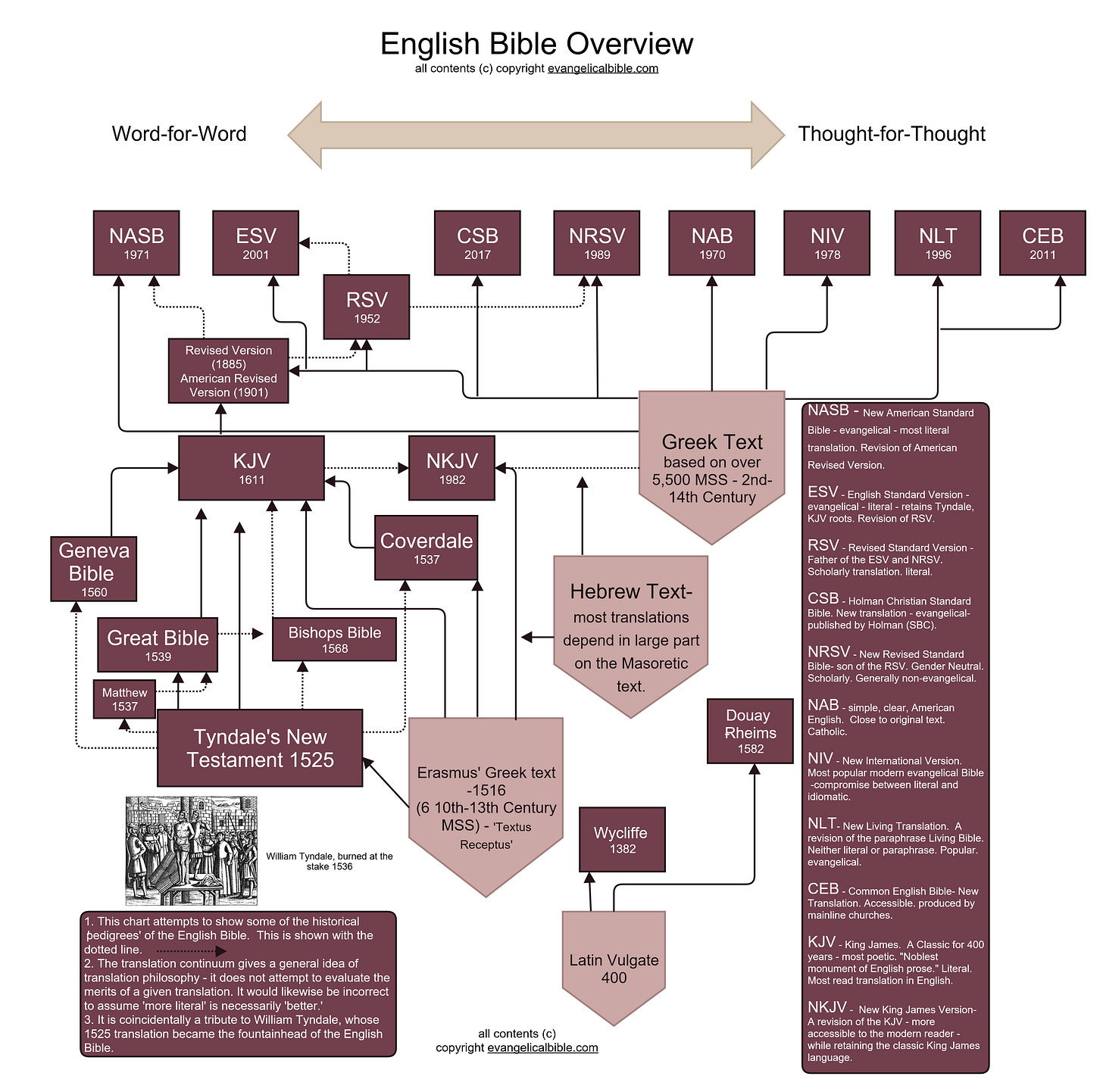

If you’re reading this and live in Europe, North America, English-speaking Africa, Australia, India, or anywhere the English language has had a significant presence, your cultural memory is heavily influenced by William Tyndale’s New Testament, the King James Bible, and overall Early Modern English. This influence is amplified in the U.K. and U.S. Over half of our Bibles today in their goals include maintaining that Tyndale-King James tradition: the RSV, NRSV, ESV, NKJV, NASB, REB, NRSVue, MEV, etc. There is a certain way the Bible sounds in our culture, and this is the point where I made a great misconception. I had fallen into the idea that our Bibles needed to be unhinged from the Tyndale-King James tradition. I believed, mistakenly, that this led to our Bibles being somehow less-accurate because many translations seek to keep the lineage of how the Scriptures sound in our tongue alive.

I was missing the blessing this rich gift is. It’s really not just the KJV lineage these translations are maintaining, even the KJV has its lineage in its predecessors: the Great Bible of 1539, the Bishop’s Bible of 1568, and many important works before that. Before the translation committee of the KJV was even formed, there was an English Bible tradition and cultural memory. Primarily, what the modern translations in this lineage are preserving is our collective cultural memory of the Scriptures as the English Church, and this cannot be understated. It is no mistake that a plethora of phrases and truths of Scripture survive in commonspeak to this day, even in our post-Christian culture. Here are some examples:

Matthew 7:12: Most people know the “Golden rule”: “do unto others as you would have them do to you.”

Genesis 3:19: “Ashes to Ashes, dust to dust” reminds our culture that they are not invincible, life is fleeting.

Matthew 5:13: If someone is a person who is “salt of the earth” people are recognizing their honesty or integrity, it is evidence of God’s prevenient grace working in them.

Genesis 4:9: Being your “brother’s keeper,” taking responsibility for others.

Luke 10:30: A Good Samaritan is someone who is selfless, caring for another and expecting nothing in return.

John 8:7: Not “casting the first stone” is a universally recognized principle about judgement.

John 8:32: “The truth will set you free.”

Acts 20:35: “It is better to give than receive.”

I could go on and on, but I think my point is made. The unmeasurable impact of an entire language across seas having a pan-cultural conscience filled with the word of God is a blessing. To some, this may seem trivial, but I believe that Scripture is powerful enough that even when used in ignorance or as part of mere cultural memory it is a catalyst for the Holy Spirit to reprove, correct, and teach, and train in righteousness (2 Tim 3:16). Put simply, our culture is better for having this lineage, and it ought to be preserved - with appropriate measure to updating for accuracy.

My concerns about how this affects the accuracy of translations is not unwarranted. After all, the English language has changed considerably over time. This is how I almost came to the point that I considered it gain if suddenly all we had were fresh translations. However, my mistake was I overcorrected. Critically considering the translations in the Tyndale-KJV tradition such as the ESV and NRSV, this is exactly what they do - they maintain much of the majesty and keep the cultural memory of Scripture alive as part of our DNA while making sure the translation stays within the bounds of modern scholarship, and they do a great job at this task. In fact, the ESV and NRSV are not from the ground-up translations. They are updates of the RSV, which they have over 90% text in common with. The RSV itself was a 1950’s update to a pair of translations called the (England) Revised Version (1885) and American Standard Version (1901), themselves updates of the King James (which had several updates of its own between 1611-1769).

The job of these updates is not only to maintain the legacy and replace archaic words, it is also to account for the latest scholarship and manuscript evidence, so we can be assured that some of the best scholars in their respective languages are maintaining the accuracy of text in our modern language. Despite these updates, it is impressive that a large amount of the text has not been changed significantly in the nearly 400 years since the KJV was published. For example, the ESV only differs from the RSV in 8% of its text. The scholarship of the KJV, relative to its time, and the scholarship of the works that influenced it, have done much to allow us to maintain the cultural memory over large swaths of time even with updates to the translation corpus.

Fresh Translations

While I am much more comfortable with Bibles that translate in the English Bible tradition now, I still believe there is great value and power in a translation that loses those shackles and allows itself the ability to harness the modern English language completely. That is the primary downside of translating in the English Bible tradition, there are certain limitations to the liberty of changing translation before it crosses the line of being new altogether.

Let’s take John 1:14 for example. The ESV, translating in the Tyndale-KJV tradition renders it as such:

“And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.”

Now, let’s see how the CSB renders that passage:

“The Word became flesh and dwelt among us. We observed his glory, the glory as the one and only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth.”

Notice the difference between we have seen (ESV) and we observed (CSB). The Greek word there, ἐθεασάμεθα, is defined in the Louw-Nida Lexicon as “to observe something with continuity and attention, often with the implication that what is observed is something unusual—‘to observe, to be a spectator of, to look at.’” The English word seen is a fine translation and is part of how we truly speak (ie. “We have seen the glory of God!”). This translation denotes this is someone real, that Jesus was and is real, someone to be experienced and seen. John, as the “disciple Jesus loved,” knew how human and real Jesus was perhaps better than almost anyone. Seen conveys that well.

Yet, observed captures something about ἐθεασάμεθα that simply seeing does not, the foreignness to humanity of what is being seen (the glory of God made manifest) is rendered well with observed. Observed is saying it is something that needs to be studied and digested to be understood, this is not something merely human. For John, the writer of this passage, he walked with Jesus, saw his miracles, experienced the events of the Resurrection, and knew the glory of God in Christ Jesus. There is surely need for both renderings to help us to understand the Greek in English.

Some may argue that can be solved by a footnote, or studying the Greek language, and that’s true. However, it is the places that fresh translations jar us that we need. Looking up the meaning of a word in a lexicon doesn’t have quite the same effect as hearing it while reading in context. Another great example of this is Philippians 2:6:

“Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped…” - Phil 2:5-6 (ESV)

“Adopt the same attitude as that of Christ Jesus, who, existing in the form of God, did not consider equality with God as something to be exploited.” - Phil 2:5-6 (CSB)

Again, grasped is a fine translation and is certainly the way it is supposed to sound, but the meaning of grasped has evolved. In Webster’s 1828 Dictionary grasped was defined as: “Seized with the hands or arms; embraced; held; possessed.” Merriam-Webster currently defines grasp as: “to take or seize eagerly; to clasp or embrace especially with the fingers or arms; to lay hold of with the mind.” Grasp can almost mean ‘to understand.’ Meanwhile, exploited is defined as, “used for someone's advantage, especially, of a person: unfairly or meanly used for another's advantage.” The Greek there, ἁρπαγμὸν, seems to indicate taking something by force, as if to plunder or rob, to take what is not yours. Exploit seems to capture that meaning better than grasp, however it lacks the callback to “grasping the glory of God” we all know is part of our grammatical DNA. And exploit jars you a bit more when you read - it is a heavy-hitting word. Both are acceptable, and both are needed.

Let’s look at one more practical example:

“But watch yourselves lest your hearts be weighed down with dissipation and drunkenness and cares of this life, and that day come upon you suddenly like a trap.” - Luke 21:34 (ESV)

“Be on your guard, so that your minds are not dulled from carousing, drunkenness, and worries of life, or that day will come on you unexpectedly like a trap.” - Luke 21:34 (CSB)

Notice the parts of each I have italicized. The CSB is simply clearer to my modern ears. I don’t ever recall in my life hearing someone reprimanded for their dissipated living, however I do know what happens when you go carousing.

Conclusion

So, what is the conclusion to all of this? The conclusion is we live in a unique place in time. On one hand, our society still has a very alive cultural memory of the Scriptures. That is a blessing, given to us by the beautiful liturgy, preaching, studying, and praying of the saints who went before us. On the other hand, our language has undergone a serious change. For better or worse (definitely worse), some of the beauty of the English language up to this point is eroding and being replaced. For that reason, we are in need of translations that move from the Tyndale-King James tradition and into something that aligns better with the language that is spoken by the people who will read it. Yet we also need to keep the Scriptures as we know them in our cultural DNA alive.

Please consider not simply settling for one translation, but rather have at least one that recalls the great English Bible tradition of the Tyndale-King James lineage and one that is more of a “fresh” translation. For me, that looks like using the CSB as my daily reading Bible, taking the ESV to church, and using a full suite of translations in both categories for academic endeavors and deeper study.

Maybe you’ve never ventured outside of one translation. Maybe you are already a master of biblical languages. Maybe you find yourself looking at the list below and see the translations you like in only one category, or possibly you already read a mix in both. Wherever you are coming from I hope you are encouraged to regularly engage with at least one translation in each category. Keep in mind that you are seeing two very needed perspectives as I believe our study of Scripture will be greatly enhanced by it.

Translation Options

Popular translations in the great English Bible tradition:

King James Version (KJV)

New Revised Standard Version (NRSV)

New American Standard Bible (NASB)

English Standard Version (ESV)

New King James Version (NKJV)… and more.

Popular “fresh” translations:

Christian Standard Bible (CSB)

New International Version (NIV)

New English Translation (NET)

New Living Translation (NLT)

Lexham English Bible (LEB)… and more.