Institutes of Wesleyan Religion

Is there a revival underway in Wesleyan systematic theology?

When I began studying for ordination in the Free Methodist Church, I distinctly remember seeking out Wesleyan and/or Methodist1 systematic theologies and finding, to my great disappointment, that there was not much recent work in the field of systematic theology in the Wesleyan movement at that time. John Wesley, unlike John Calvin, did not leave his followers with an Institute, or a dogmatic and systematic theology. Instead, he left them largely with sermons, hymns, and prayers. That does not mean Wesleyanism is not worthy of a systematic treatment, but that Wesleyan theology was initially grounded in the outward work of the Evangelical Revivals of the 18th century, at least more than it was in written dogmatics. But if a movement is to be theological (making claims about God) and distinct (making theological claims that in some way distinguish it from other movement’s claims), at some point those distinctions must be defined and explained, otherwise it is hard to build on the lack of permanance and pliability that necessarily accompanies ignoring theology and distinctiveness. Even early circuit riders understood carrying their “little libraries:” essential theological and devotional books that fit in their saddlebags and coat pockets.

It is necessary to say a brief word about what systematic theology is and why it is needed. Systematic theology is an attempt to present Christian dogmatic teaching in a coherent and unified manner beginning from first principles—truths about God and Scripture. As a systematic theology works outward from first principles, it seeks to bring together Christian teaching in a manner that avoids contradiction. This is an important task because if an aspect of doctrine does not comporte with the principles that precede it, a contradiction is possibly created that reveals we are believing something to be true which is not true. This is potential evidence that a theological work is misrepresenting God. (For more on the process of systematic theology, check out Gerald Bray’s essay.)

In some sense, there are certain “marks” of systematic theology in the same way thinkers articulate marks of the church. Dr. Jason Vickers, writing in Firebrand Magazine, proposes three marks of good systematic theology: 1) it begins with God, 2) it is about God, and 3) it leads to God.2 These are good guiding principles, and I believe that the last mark he proposes is infinitely important. When reading John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion, I began to notice Calvin breaking into doxology and even prayer in the midst of his grand systematic theology. Consider the following excerpt from Institutes:

To conclude once for all, whenever we call God the Creator of heaven and earth, let us at the same time bear in mind that the dispensation of all those things which he has made is in his own hand and power and that we are indeed his children, whom he has received into his faithful protection to nourish and educate. We are therefore to await the fullness of all good things from him alone and to trust completely that he will never leave us destitute of what we need for salvation, and to hang our hopes on none but him! We are therefore, also, to petition him for whatever we desire; and we are to recognize as a blessing from him, and thankfully to acknowledge, every benefit that falls to our share. So, invited by the great sweetness of his beneficence and goodness, let us study to love and serve him with all our heart.3

No, my friends, Calvin’s Institutes is not the dry, hopeless work of predestinarian horror some may have led you to believe. His work clearly led him to God, and still leads others to God to this day, which is why it stands at the forefront of systematic theologies ever written, finer points of disagreement aside. If we are to think about systematic theologies in the Wesleyan tradition that coherently bear witness to God, they should bear these marks as well.

Historic Methodist Systematic Theologies

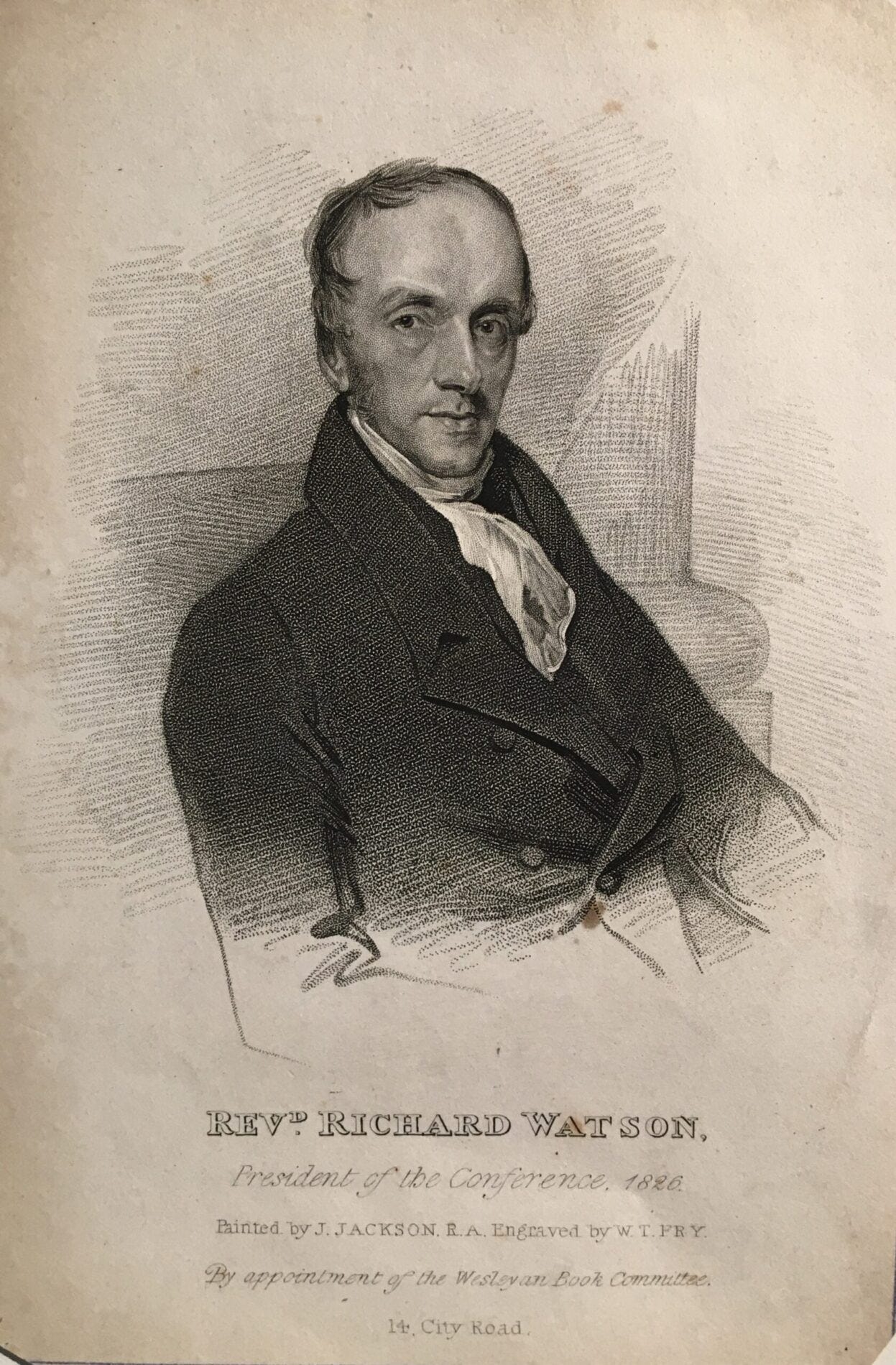

While I had not found recent works of Wesleyan systematic theology when I had looked previously, what I did find when I looked for systematic theologies many years ago was a treasure trove of now oft-neglected works: it turns out there is actually a rich history of systematic theology in Methodism! Buying one of Logos Bible Software’s “Methodist & Wesleyan Starter Packs” for example will bring you into possession of several Methodist systematic theologies such as William Burt Pope’s Compendium of Christian Theology (1877-1879), Miner Raymond’s Systematic Theology (1879), Thomas O. Summers’ Systematic Theology (1888), John Miley’s Systematic Theology (1892), Richard Watson’s Theological Institutes (1823), or H. Orton Wiley’s Christian Theology (1940).

“[William Burt Pope’s Compendium of Christian Theology is] one of the greatest systematic theologies written from a Wesleyan or Arminian perspective.” - Wayne Grudem

Did you notice a pattern as I listed off these seminal works? Aside from Mr. Wiley’s, they are all 19th-century works! The 19th century was, in some manner, the century of Wesleyan systematic theology. Wayne Grudem, the modern Calvinist systematic theologian, took time to commend Pope’s Compendium in his own recent systematic theology, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine. In the same volume, he also applauded Wiley’s 1940 systematic. One Methodist work that seems to stand out above all, however, is Richard Watson’s Institutes. It was the standard text for ministers-in-training in both American and British Methodism for decades after being published. Dr. Ben Witherington III contends that Watson’s systematic was invaluable for Welseyanism because, “He showed that Methodist theology was not just "lay" theology or "revival" preaching but was just as capable of producing systematics as the Lutheran or Calvinist traditions—systematics that made sense especially of the doctrine of salvation without compromising the doctirnes of oringial sin, God’s soveringinity and grace, or human responsibility for human actions and for responding to the Gospel.”4 In other words, Watson’s systematic theology takes Wesleyan theology seriously and presents a coherent vision for a comprehensive theology.

Based on the historical evidence, a systematic or holistic look at theology is not foreign to Methodist and Wesleyan thought. I’ve unfortunately heard it remarked time and time again that “Wesley was not a systematic theologian, so ‘we’ should not have a systematic theology.” Yet this criticism ignores what systematic theology actually is for a caticure and opens Wesleyan theology to all sorts of strange doctrines based on fallible human experience. It is telling that, after Wesley, his heirs began work on several systematic theologies which dotted the 19th century. This was no mistake or fluke—rather, they viewed articulating a holistic and coherent theology as essential to continuing Wesley’s movement and justifying Wesleyan soteriology as coherent with classical Christian orthodoxy. If Wesleyan theology was not coherent, then they were doing little good giving it to the world, so they set about arguing that it did cohere. Yet, aside from Wiley’s three-volume work and a few one-volume works, Wesleyan theology largely conceded the space of systematic theology to other theological traditions in the 20th and 21st centuries. The 20th century largely failed to see a definitive systematic theology published that could steer the entire tradition through the 20th century. Perhaps this is one of the reasons Methodism has had the theological tumult that it has experienced.

The 20th century was not a silent century, however. Wiley published his systematic work, and some others will be mentioned in due time. Additionally, some work was done in the areas of paleo-orthodoxy and Wesley studies that has relevance to this conversation. It is beneficial to mention some of the work done in these areas before looking at the current state of Wesleyan systematic publishing.

Thomas Oden

Paleo-Orthodoxy

When I began seminary at Asbury Theological Seminary, our standard systematic theology text was Thomas Oden’s Classic Christianity. It is a magnificent work, to be sure, but not uniquely Wesleyan, despite Oden being a Methodist. Oden’s systematic theology, originally released in three volumes from 1987-1992, is his magnum opus of paleo-orthodoxy. Paleo-orthodoxy is a movement that focuses on the first 1000 years of church history, before the Great Schism, to find Christian theological consensus. What is coined paleo-orthodoxy includes the influence of many Wesleyan theologians, but is not exclusive to Wesleyans by any stretch. Paleo-orthodox scholars use the basis of the consensus of the first millennium and trace a thread through the rest of Church history to construct an “ancient” (paleo) orthodoxy. Much like the task of systematic theology itself begins from first principles and works outward, paleo-orthodoxy begins from a place of Christian consensus and works outward. For example, in Oden’s systematic theology, he’ll regularly cite figures as distinct as Cyril of Jerusalem, Augustine of Hippo, Luther, Calvin, Wesley, and Kierkegaard on the same page and for a particular doctrine! It is a unique, thoughtful, and helpful project to be sure, but Oden’s systematic theology is not exactly a Wesleyan systematic theology, though a Wesleyan may find himself justified in subscribing to it. Rather, it is a distinctly paleo-orthodox systematic theology.

Given the goals of paleo-orthodoxy, it may seem like the pinnacle of theology. “Why should we be Wesleyan, or Calvinist, or Lutheran?” you may ask, “Let’s just be paleo-orthodox!” Unfortunately, there are three glaring flaws in Oden’s project:

There was no perfect Christian consensus before the Great Schism.

Inevitably, a modern theologian, even a paleo-orthodox one, must at some point interpret the early church, which invariably leads to multiple interpretations.

There are areas of theology that are not explicitly addressed by the early church.

These flaws do not make Oden’s work dismissible by any means, but it does place natural limits on it. The reason this is important to note is that Wesley himself contended that his theology sought to return to “primitive Christianity.”5 By this, he meant the apostolic and early church. Therefore, anyone attempting to undertake a Wesleyan systematic theology must engage in the task of retrieving primitive Christian beliefs to some degree. Yet, retrieval is not necessarily the primary task of Wesleyan theology, unlike paleo-orthodoxy.

Wesleyan Systematic Theology—Not Merely John Wesley Systematized

Oden also has another work, John Wesley's Teachings. This project was an attempt to explain, or systematize, John Wesley’s teachings. The focus of Oden’s work here, however, was to condense the teaching found in the expansive works of John Wesley into a digestible theology. In many ways, it mimics a systematic theology. But it is not a Wesleyan systematic theology, but a systematizing of John Wesley’s personal theology based on what he wrote. Dr. Ken Collins has also completed a contemporary work titled The Theology of John Wesley, and there are other dogmatic sketches of Wesley’s theology widely available. This field is often called Wesley studies. These works in the field of Wesley studies are not equivalent to systematic theology because systematic theology is a holistic theological task, touching on doctrines Wesley may have written little about, or didn’t even address. This does not mean that Wesley had unorthodox views on the doctrines he rarely addressed or did not address, but it is simply a recognition that he never authored a systematic theology himself, so any task to systematize his theology does not rise to the definition of a true systematic theology. There is much more to be addressed. Indeed, if you would have asked Welsey, “What do you think of this doctrine you have never pubicly addressed?,” his response would be something like: “I believe the doctrine [I] preach to be the very doctrine of the Church of England; indeed, the fundamental doctrine of the Church, plainly laid down in her Articles, Homilies, and Liturgy.”6

The benefit of the surge in Wesley studies in the 20th and 21st centuries is that there has been a lot of theological work done in the areas of theology that are uniquely Wesleyan. The task of a Wesleyan systematic theology, as stated before, includes representing the Wesleyan theological tradition as a coherent tradition amid its unique theological claims. Any new systematic theology would benefit greatly from the recent work done in the field of Wesley studies.

A Revival Of Wesleyan Systematic Theology?

Over the past five years, I have noticed Wesleyan systematic theologies begin to be published. Some with fanfare, others quietly gaining traction. It hit me when I was watching PlainSpoken’s recent interview with Dr. John Oswalt (found below)—there have been at least five Wesleyan systematic theologies released, begun to release, or announced to be released just in the past three years or so (if you know of any more, please let me know). Given the timeline we explored earlier, where the 19th century was the golden age of systematic theology, followed by a sparse 20th century, this sudden resurgence of systematic theology is hugely significant for Wesleyanism. I have attempted to illustrate how divergent the last five years are, even compared to the 19th century, with the timeline below. Inevitably, the timeline is not comprehensive and will be missing a work or two (hopefully not your favorite), but nonetheless illustrates the massive uptick in writing and publishing since 2023.

As I have not had the time to read any of these new systematic theologies, I will, for now, forgo an attempt to review them or recommend them. Several of them are multi-volume works that are to be released in volumes in the coming years. It will take time to see if any of them stand the test of time like Watson’s Institutes, which uniquely preceded these new systematics by being republished in 2018 by Lexham Press in a new edition with an introduction by noted Methodist New Testament scholar Ben Witherington III. Without any additional commentary, I will simply list these recent systematics for the record.

1. Christian Theology by T.A. Noble (2023-future)

2. Holiness: A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Theology by Chris Bounds, Caleb T. Friedeman, and Matthew Ian Ayars (2023)

3. Fundamental Wesleyan Systematic Theology by Vic Reasoner (2024)

4. Holy Love: A Wesleyan Systematic Theology eds. John Oswalt, Christianne Albertson, and Matthew Ian Ayars (2024-future)

5. Love Divine: A Wesleyan Systematic Theology by Jason Vickers and Thomas H. McCall (2026)

Is This A Revival?

In the five new systematic theologies listed above, we see several different visions emerge. Some of the brightest scholars in the Wesleyan world are contributing to these volumes. It certainly does feel like there is a revival of the writing and publishing of Wesleyan systematic theology. Yet, I can’t help but think there are other questions to be asked that are more important. Will any of these stand the test of time? Will they have a lasting impact on Wesleyan theology that goes beyond academia and preserves a traditional understanding of Wesleyanism? Will one or more of them play a role similar to Watson’s Institutes, becoming a modern standard universally upheld and upholding us? Only time will tell, but it is an exciting time!

If you enjoyed this article, you will likely enjoy learning more about systematic theology with Jeffrey Rickman and Dr. John Oswalt:

For the sake of this post, I will use Wesleyan and Methodist interchangeably. However, I do want to note there is a difference in these terms in regards to systematic theology. A Methodist systematic theology will likely have a distinctly Methodist conclusion. We see this in the historic Methodist systematics like Richard Watson and Adam Clarke. A Wesleyan systematic theology, however, may not be drawn to the same conclusion about historic Methodist practice. This is just one example of how these terms could differ if parsed. Given that “Wesleyan” is a broader term inclusive of certain Anglicans and Pentecostals, a “Wesleyan” systematic theology may not be Methodist, properly speaking.

Vickers, Jason E. “On Christian Perfection: The Role of Systematic Theology.” Firebrand Magazine, Feb. 04, 2025. https://firebrandmag.com/articles/on-christian-perfection-the-role-of-systematic-theology

Calvin, John. Institutes of the Christian Religion. Edited by John T. McNeill, Translated by Ford Lewis Battles, vol. 1, Westminster John Knox Press, 2011, 182.

Witherington III, Ben. “Introduction: Richard Watson and His Institutes” in Richard Watson, Theological Institutes, vol. 1, Lexham Press, 2018, xii-xiv.

For example, Wesley’s sermon “On Laying The Foundation Of The New Chapel, Near The City-Road, London.” https://wesley.nnu.edu/john-wesley/the-sermons-of-john-wesley-1872-edition/sermon-132-on-laying-the-foundation-of-the-new-chapel-near-the-city-road-london/

Wesley, “On Laying The Foundation Of The New Chapel…”.

I am here for all of it!!! I’ve been having the systematics conversation with @Joshua Toepper for the last year.

Oden does great work. Although I think a robust biblical theology is far more important than a systematic theology and far more in the tradition of Wesleyan theology.