The Doctrine of Emeth

C.S. Lewis and The Sufficiency of Christ

It is a bit of a tall-tale, but some people religiously contend that C.S. Lewis was a “Christian Universalist.” Christian Universalism is a heretical doctrine that posits all will be saved in the end, even those in Hell. Some Christian Universalists contend there is not even a such thing as Hell. You do not have to look any further than Lewis’ seminal work The Problem of Pain to find a clear affirmation of the doctrine of Hell and the reality of eternal separation from God, even while he humbly admits he would prefer it not to be:

And it has been admitted throughout that man has free will and that all gifts to him are therefore two-edged. From these premises it follows directly that the Divine labour to redeem the world cannot be certain of succeeding as regards every individual soul. Some will not be redeemed. There is no doctrine which I would more willingly remove from Christianity than this, if it lay in my power. But it has the full support of Scripture and, specially, of Our Lord’s own words; it has always been held by Christendom; and it has the support of reason. If a game is played, it must be possible to lose it. If the happiness of a creature lies in self-surrender, no one can make that surrender but himself (though many can help him to make it) and he may refuse.1

Then, Lewis admits that he wishes he could confess all will be saved, but cannot, for the violence it does to the doctrine of free will is extreme.

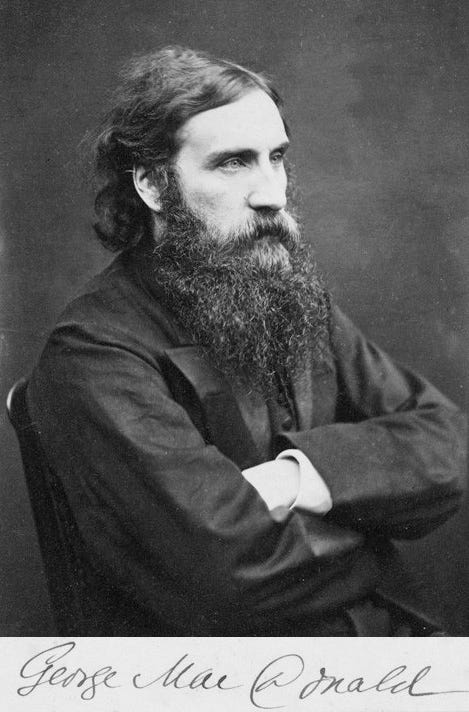

George MacDonald

Though Lewis was clear that he stood on orthodox Christian teaching, it is fair to say he was a hopeful universalist—one who recognizes Christianity does not explicitly teach Universalism, but still has a small hope that the mercy of God will extend to all men so they may be saved. A hopeful universalist essentially says: “God holds all the cards, and we do not see all the cards. The cards we do see do not leave an opening for universalism. Rationally, therefore, we ought to leave a small possibility that all men will be saved based on some cards, but concede man has no such knowledge and the cards are not in favor.”

Lewis had something of a fascination with purported Universalist clergyman and author George MacDonald, who appears as a character in Lewis’ The Great Divorce. In the book, MacDonald ironically declares to the main character that man actually does not get to know the intricacies of who will be saved. So, Lewis makes even MacDonald retreat from Universalism to being a mere hopeful universalist in the fictional literary afterlife version of himself.

Given the above context, I will state my understanding of the matter plainly: C.S. Lewis is not a Christian Universalist. He clearly affirmed the doctrine of eternal Hell, even though he was clear about his discomfort with the doctrine. I felt the preceding context was necessary for the discussion that will follow, and I hope you found it helpful. Now that the discussion about universalism has been had, and we have dispelled of the rumors surrounding it: what do we do with Emeth?

If you have not read The Chronicles of Narnia, especially The Last Battle, consider this your spoiler warning. Beyond this point, major plot points will be discussed.

Emeth

Emeth is a curious figure. He appears in The Last Battle as a soldier in the Calormen Army. The army is brought to where the supposed “one god” called “Tashlan” is, residing in a stable. They parade this supposed god around. Emeth, enraged and recognizing this is not Tash or any other god, volunteers to enter. Shortly after he enters, a Calormen soldier is ejected from the stable. The false prophets lead everyone to believe this was Emeth, but actually it was someone they had setup to kill anyone who enters so they could not report the deception. When encountered by the Narnians Emeth reveals he fought the soldier and threw him out of the stable. Emeth deduced that anyone who would ambush someone seeking the true God was a villain. But when Emeth came about, he found he was not inside a stable, but in a country and promptly met Aslan.

Emeth Receives The Sacraments

Emeth immediately recognizes that Aslan is the true God, and admits sorrow in his heart for having served Tash. He expects he will die in Aslan’s presence, but considers this a great thing to have seen Aslan. Aslan, instead of killing Emeth, licks him. Do not miss this, this is not a silly detail Lewis includes. Aslan baptizes Emeth with the Word. This allegory for the Word is straight from Scripture: “Death and life are in the power of the tongue, and those who love it will eat its fruits” (Proverbs 18:21). This is the same tongue that licked Lucy in Prince Caspian, which make her Aslan’s beloved. This is the same tongue that licked Caspian’s dead body, resurrecting him (Narnia’s Lazarus moment). We see this sacrament in Narnia given to humans. I assume this is because the animals of Narnia have sacraments of their own.

Aslan explains to Emeth that though he had believed he was serving Tash, he was not, because Emeth was seeking Truth and did not do the evil that would be part of being a Tash-follower. Echoing Jeremiah 29:13, Matthew 6:33, Matthew 7:7, and a whole slew of Scripture, Aslan says, “Unless thy desire had been for me thou wouldst not have sought so long and so truly. For all find what they truly seek.”2

Then Aslan breathes on Emeth. This is Emeth’s First Communion. While the Eucharist was inaugurated at the Last Supper, the crucifixion had not happened yet, there was no sacrifice to remember. It was not until after the Resurrection, when Jesus breathed on the disciples to receive the Holy Spirit, did the sacramental ministry of the Church begin, for the disciples saw Jesus’ wounds, enabling the anamnesis he commanded to accompany the Eucharist, true remembering. Then Jesus breathed on them, a purely spiritual Eucharist, where the Apsotles received the Holy Spirit and the ministry of pardon was imparted to them, a chief benefit of the Eucharist (John 20:19-23). In Narnia, Aslan regularly did sacramental acts with his breath that mirror the Eucharist: creation, recreation, judgment, and strengthening. The Eucharist is the Word received. When existence receives the Word, creation occurs (John 1:2-3). When fallen things receive the Word, they are recreated (Rev 21:3-4). When rebellious things receive the Word, they receive judgment (1 Cor 11:27-29). When those who are God’s beloved receive again the Word, they are strengthened (1 Cor 11:26). Emeth became God’s beloved when Aslan licked him and was strengthened by Aslan’s breath, causing him to immediately standing up in power!

In summary, Emeth has contrition, repents, is baptized, and receives the Eucharist. Then Aslan promised Emeth he would be with Aslan in Aslan’s Country, mirroring Christ’s promise to the Thief on the Cross (Luke 23:39-43).

Universalism Considered

As demonstrated, Emeth is not an allegory for Universalism—that all will be invited. If he were such an allegory, all Calormen who worshiped Tash would be able to enter Aslan’s Country. In The Last Battle, Aslan explicitly rejects all true followers of Tash and accepts only Emeth. Emeth even has a hand in this when he ejects the Calorman soldier from the stable. Talk about sovereignty. This is not Universalism by any stretch because every Calorman follower of Tash is damned. Only Emeth is saved.

Inclusivism Considered

“Lord, is it then true, as the Ape said, that thou and Tash are one?”

The Lion growled so that the earth shook (but his wrath was not against me) and said, “It is false. Not because he and I are one, but because we are opposites, I take to me the services which thou has done to him.”3

The character of Emeth is also not advancing inclusivism—the idea that God saves some in other religions, or some will be invited. Lewis, via Aslan, makes it clear: Emeth was not following Tash, not really. He did not hold to any of the tenants of the Calormen religion. Inclusivism would posit that even though Emeth served Tash, Aslan saved Emeth though he got some things wrong here and there. This implies the religion of Tash got just enough right that Emeth could squeeze in, so to speak. Again, this is clearly not the case because this is not an offer available to all Tash-followers who got some things right. This was not a case of the false religion getting some things right about God, just enough that some folks who adhere to it sneak in. Aslan makes it so clear this is not possible that the earth shakes. Tash is his complete opposite. His enemy. A vain mockery. Those who serve Tash receive wrath. Only Emeth is being invited.

The inclusivist says Emeth is being saved because of some of what he did for Tash. The reality is Emeth is being saved because of what he did not do for Tash, but for his heart for the True God.

A Reverse Hypocrite

In researching the case of Emeth I was surprised to find an ally in the Reformed theologian Douglas Wilson. He helpfully coins Emeth as a “reverse hypocrite.” What he means is Emeth’s claim is that he is serving Tash, but in actuality he is serving Aslan. Wilson puts it aptly, “Emeth had been going in the "wrong" direction, as far as Tash was concerned, since he was a boy. As far as Tash was concerned, Emeth had been a heretic for a long time.”4

We recognize the category of a hypocrite easily enough. For example, if someone claims to be a Christian, but consistently rejects the teachings of Christ by his actions, he is clearly a hypocrite. But can this go the other way? Can someone claim to serve another god, but reject that god so consistently that he is actually shown to be serving Christ? It seems rationally possible.

I do think we have to be careful with this concept of a reverse hypocrite, because it can be easily misunderstood to create a doctrine of “anonymous Christians,” as if there are people in all sorts of religions who are actually Christians, and they do not realize it. The example of Emeth is not necessarily proposing this because when Emeth encounters Aslan he recognizes Aslan, which is who Emeth has been seeking all along. He does not mistake Aslan for Tash. He does not wish to change Aslan to Tash. In confidence, he kneels before Aslan. He accepts the Truth. A true Tash-follower would never do such a thing. To put it plainly, when Emeth comes face-to-face with the True God, he willingly follows Him “further in and further up.” This reveals Emeth’s loyalties are not divided and he truly serves and even loves Aslan.

This is a necessary caution because Emeth does not adopt a secret identity. After encountering Aslan, he follows Him explicitly. He is not anonymous.

Is This Creating an Exception?

Jesus said to him, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father, but by me.” - John 14:6 (RSV)

It is fair to ask: is Lewis making a case for exceptions to the general principles of salvation in the example of Emeth? After all, we believe salvation is by Christ alone. I think it is clear he is not creating an exception to Christ alone. Aslan is not carving out an exception to welcome Emeth into Aslan’s Country, and God does not make exceptions to salvation through Christ, either. God is sovereign and has foreknowledge of every man’s use of his own free will. Instead, what Emeth is an example of is what can be called the extraordinary means of salvation.

The ordinary means of salvation are cited often in Scripture and in our theologies. When describing the ordinary means we use words like repentance, faith, Baptism, the Lord’s Supper, etc. We attempt to articulate the ‘how’ of salvation in the ordo salutis, the order of salvation. But Scripture is also clear that God often saves men without all or any of the ordinary means of salvation. Two examples in Scripture are most profound: the thief on the cross and those rescued from Hades.

In both of these examples, God in Christ is not saving those who reject Him, rather He has graciously extended the offer of salvation to those who would otherwise not have the opportunity to respond to Him without this extension of His grace. The descent to Hades speaks the most profoundly of this. “If I make my bed in Hades,” the Psalmist declares, “you are there!” This makes it clear: there is nowhere God’s offer of grace does not extend.

This is crucial because an exception would mean that salvation is not occurring through the name of Jesus, not by Christ alone. In the extraordinary means, however, Jesus goes to the one being offered God’s grace, bringing the hope of salvation to man. This is by Christ alone! It is actually only extraordinary to us, because we see the “ordinary” means of grace and regularize them. To God, this is the same outworking of the incarnation of Christ: God coming to man to reconcile man to God. It is not actually ‘extra-ordinary’ because God’s saving grace is always extraordinary from man’s perspective because He offers reconciliation to man. But from God’s perspective, His work of saving and reconciling is always ‘ordinary.’ This is what He does.

This, I believe, is why Lewis ends Emeth’s encounter with Aslan with the promise that Emeth will see Aslan again. This is the promise Jesus made to the Thief on the Cross, as I mentioned. Lewis is directly linking Emeth’s salvation with the Thief’s salvation.

This is where many interpreters of Lewis fail. As we discussed, Lewis is also careful to make it clear that Emeth receives the sacraments. Scripture does not unambiguously demonstrate the Thief received the sacraments physically, but he certainly did spiritually: his Baptism was in the blood dripping from him on the cross as he made his confession and his Eucharist was in the Word of eternal promise coming into his body directly from Christ’s mouth through his ears. The means may be extraordinary, but it is the same salvation we all receive from Christ. Maybe I am doing a disservice by saying it is extraordinary. After all we discussed how both Emeth and the Thief received the sacraments. It may be more prudent to simply say this isn’t the normal way things happen from our human perspective, but it is the same things happening.

The Sufficiency of Christ

When it comes down to it, the character of Emeth expresses Lewis’ profound hope in the sufficiency of Christ for salvation.

In modernism, there is severe doubt about the sufficiency of Christ alone for salvation. Liberal academics and theologians, popular authors, and those lacking sufficient faith are constantly looking outside of Christ to include others in salvation. They, like Lewis, are uncomfortable with eternal Hell. They might even have ‘good’ intentions. Yet, they do not yield to God as Lewis did, instead they corrupt the Gospel. This is, of course, a misplaced hope: there is salvation in no other name but the name of Jesus. It demonstrates a lack of true faith that God is both just and good.

And there is salvation in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given among men by which we must be saved. - Acts 4:12 (RSV)

Lewis offers us a helpful corrective to modernity, demonstrating how to have faith despite our faulty feelings. Do we not have faith that Christ is sufficient to save all who deserve salvation? Do we not think Christ will actually go to those with hearts aligned with God and offer Himself? We need this sort of faith.

When we are confronted with the question, “What is the eternal fate of those who never hear the Gospel in their lifetime?” The answer: Christ is sufficient.

“What about my Muslim neighbor, who seems more ‘Christian’ than some Christians?” Christ is sufficient.

Whatever the case Christ is sufficient. Jesus Christ Himself said directly to St. Paul, “My grace is sufficient for you” (2 Cor 12:9). We dare not doubt our Lord.

The answer is never Christ is not sufficient, which is what Liberal Christianity argues for. Christ’s salvation attested to in the Scriptures is not sufficient or at least is too restrictive, they argue, so we (humans) have to expand the concept of God’s salvation. This is a grave error. If it is not Christ’s salvation, it is not God’s salvation. It isn’t salvation at all and leads to false hope.

C.S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain (HarperOne, 2001), 119-120.

C.S. Lewis, The Last Battle (HarperCollins, 1956), 189

Lewis, The Last Battle, 188-189.

Douglas Wilson, “The Salvation of Emeth” on Blog & Mablog, January 7, 2019. https://dougwils.com/books-and-culture/books/the-salvation-of-emeth.html