Reformed-Methodist

The Forgotten History of the Methodist Influence on the Reformed Episcopal Church

When I was confirmed as an Anglican, I joined the Anglican Church in North America, a province founded in 2008. However, the formation of the ACNA has a long and complicated history that stretches long before 2008. Much like organizations such as the Wesleyan Covenant Association were working behind the scenes in United Methodism to advance orthodoxy, the Common Cause Partnership (CCP) filled a similar role in relation to the Episcopal Church. What was different about the CCP was that it included other Anglican denominations alongside conservative Episcopalians, chief among them the Reformed Episcopal Church (REC), a small Anglican denomination that separated from the Episcopal Church in 1873. When the members of the CCP were forming into a larger province, the REC joined the ACNA, maintaining a separate structure but participating alongside the whole.

Initially, the REC was notoriously low-church. As one REC priest puts it, the early REC was “dispensationalism, a truncated prayer book, and black preaching gowns.”1 An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church describes the REC as follows: “This body rejects baptismal regeneration, any sacerdotalism with the Lord’s Supper, apostolic succession in the historic episcopate, and does not participate inn [sic] the ecumenical movement.”2 The definition is antiquated, and, as I will explore, that last bit about ecumenism is entirely contrived. The context of the founding of the REC centers around the controversy of the Oxford Movement: a renewed focus on the Catholic elements of the Anglican identity. In 19th century America, the perception was this renewed focus was to the detriment of the Protestant aspects of Anglican identity, and some felt endangered the faithful witness of what was then called the Protestant Episcopal Church, at the time America’s sole Anglican province (now the Episcopal Church). The founding of the REC was the reaction to this movement. Since the 19th Century, the REC has moved away from its original identity, especially in its most recent generations, claiming a more classical Anglican identity consistent with an Old High-Church expression of Anglicanism. What I will be exploring in this article is the close and surprising connection the REC had with Methodism in its early days.

George David Cummins

George David Cummins’ experience with Methodism began long before his birth. His grandfather converted under the preaching of Bishop Francis Asbury in Kent County, Maryland. However, the family remained Anglican. Cummins attended Dickinson College where a revival took place in April of 1839 under the preaching of Methodists. Cummins was greatly moved by this revival and consecrated himself to the Lord, responding to a call to ministry, and joined the Methodist Episcopal Church. His mother, widowed when George was four, also married a Methodist minister around this time.

In 1842, at just 20 years old, George was appointed to a circuit as a licensed minister in Maryland with the MEC. By all accounts, he served his circuit faithfully and hosted several camp meetings, including for African-Americans, who often attended his preaching. He remarked that his circuit was so busy that he preached almost daily. In 1844, the MEC sent him to preach in Jefferson County, present day West Virginia. Yet, he continued in his duties, even picking up other circuits and preaching many camp meetings and revivals. Apparently, Cummins was an electric preacher. One described a scene where he was preaching to a largely educated group, saying, “they were not able to resist the wisdom and the spirit by which he spake.” An Episcopal minister, hearing Cummins at this revival, said, “If that young man lives, he will be heard of throughout the length and breadth of this land.”

Though he was a skilled preacher and it is reported many came to the Lord under his ministry, his years as a circuit rider seemed to ignite in him a deep desire to pastor a single congregation, and also made him long for the liturgy of the Protestant Episcopal Church of his youth. In March of 1845 he departed his itinerant duties with the MEC and sought to study under Bishop Lee in the Protestant Episcopal Church and become a candidate for ministry. He again fell in love with the Anglican liturgy; he was confirmed by Lee, and after passing several exams ordained a deacon in 1845 and a presbyter on July 6th, 1847.

In his time as a presbyter and later a bishop, Cummins mentions continuing to preach in Methodist churches. He continued work as a presbyter spending stretches at parishes in cities like Chicago and San Francisco until his consecration as bishop in 1866. His election to bishop took place nearly against his will. He had just arrived in Europe on the advice of doctors, seeking an improvement to his wife’s health, when he received news he’d been elected to be assistant bishop of Kentucky. He was saddened by the news, as he knew God was calling him to accept the nomination, but he mourned the fact he would have to move on from stable parish life and once again take up a life of instability.

Cummins, through the years of his ministry, was a staunch evangelical of the low-church variety. As a bishop, he found himself at odds with the Anglo-Catholics and the Oxford Movement, which were gaining influence in the Protestant Episcopal Church at the time. “I had watched the rise and spread of the Oxford tract movement until it had leavened to a vast extent the whole English-American Episcopal Churches,” he wrote, “but I firmly believed that this school was not a growth developing from seeds within the system but a parasite fastening upon it from without and threatening its very life.” His views shifted considerably under the influence of tracts published by the counter-Oxford movement. He became convinced the prayer book needed further reform as sacerdotalism was dangerously on the rise, which he began to witness in his Kentucky parishes.

But if the dogmas of apostolic succession, baptismal regeneration, the real presence, and a human priesthood be 'another gospel,' as all Evangelical men hold and have ever held, then is it their highest and most solemn duty to cast them out of the Prayer Book, whatever may be the sacrifice.

Cummins was clearly at odds not just with the Tractarian movement, but also the classical Prayer Book tradition he once held. The influence of the radical counter-Oxford movement swayed him. Yet, being a convinced evangelical was not enough to exclude him from the spectrum of Anglican beliefs. Rather, while in New York attending the meeting of the Evangelical Alliance, Bishop Cummins took part in a joint communion service with a Presbyterian minister. This set off a firestorm, and instead of fighting what he knew would be an impending battle, Bishop Cummins determined to part ways with the Protestant Episcopal Church before trials or presentments could proceed. He and other like-minded clergy and laypeople then organized together as the REC.

His intertwining with Methodism continued as he departed the Protestant Episcopal Church and founded the Reformed Episcopal Church. It is important to note that the “reformed” in REC is not a denotation of Calvinism, but that the founders believed they were actually re-forming the Episcopal Church in a more evangelical and true sense; finishing the English Reformation where it didn’t go far enough. Hear how a Methodist newspaper described Bishop Cummins as they reported on him guest preaching in a MEC pulpit:

On Sunday evening, November 9th, Bishop Cummins occupied the pulpit of St. Paul's Methodist Episcopal Church in this city. His sermon, which was richly evangelical, was an exposition of the superior value of the knowledge of Christ to all other knowledge. At the close of his sermon a brief reference to the venerable Dr. Durbin—who was present as the means of his conversion more than thirty years ago, excited deep emotions in the congregation. Bishop Cummins should have the support of all Evangelical Episcopalians without exception; he has the sympathy of all evangelical Christians. We rejoice to see an Episcopal bishop throw compromise away, and dare to act out his honest convictions. But must he stand alone? With his strong convictions on this subject there was but one course open to Bishop Cummins, either to fight out the battle of true Christianity in the Protestant Episcopal Church or to quit it altogether…

To Cummins, the evangelical Episcopalians who departed with him, and other evangelicals, they viewed their fight as one for true Christianity against a tide of papalism and superstition. They found ardent and ready allies among the Methodists surrounding them, and who Cummins already had foundations and relationships with. His memoir reports it was actually the same day that he preached in St. Paul’s Methodist in New York—November 9th, 1873—that he made his decision to depart the Protestant Episcopal Church.

Cummins was sent by the REC General Convention as a delegate to the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1876. He was summoned to address the Conference and some of his words express his feelings toward the faith of his youth:

And above all, and this is my last thought, the great glory of Methodism today is that it is the Church for the poor, the Church of the masses; that she has reached a lower stratum of society than has been reached by any other Protestant Church in Christendom; that she has done a work for the Master in this land that no other Church has been able to do. I have often thought what would become of the poor if those who claim to be the successors of the apostles had been intrusted alone with their salvation. Methodism has been the missionary, the pioneer of the Gospel to the poor. I bear my testimony today that in one of the great States of the West, where I labored for seven years, I never could get ahead of the Methodist preacher. I never entered into the wild fastnesses of Kentucky but I found a Methodist preacher had gone before me; and I never found myself in one of those beautiful villages on the Ohio and the Mississippi, but the first sight that greeted my eyes was the small, humble Methodist church. Methodism has been an evangel to the poor, and it may take up to-day the language of her Lord and say without irreverence, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the Gospel to the poor.”

In response to his speech the Methodist bishops immediately passed a resolution establishing a reciprocal relationship with the REC, sending a delegate to their Convention. His wife, in his memoir, reports that when he arrived home from that Methodist General Conference, Bishop Cummins said the following: “I am very thankful to have been permitted to be there to day. It may be my only opportunity to express my gratitude for what I owe to that grand Church.”3

The Search for Co-Consecrators

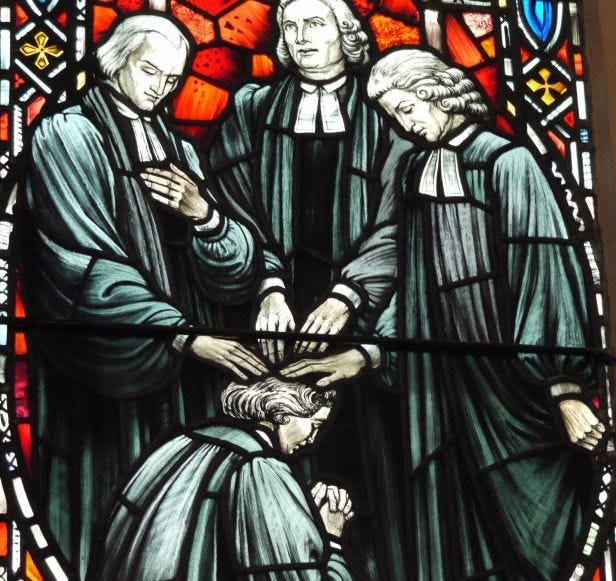

Beyond Cummins’ continued love for the Methodist faith he was raised and preached in, I was surprised to learn there is more overlap between the ministries of the Methodist Episcopal Church and the Reformed Episcopal Church. Of particular interest is that in the beginning of the REC, MEC bishops functioned as co-consecrators at episcopal consecrations on at least two occasions. This makes sense as the early REC and Methodism both believed in presbyterial succession as opposed to episcopal succession. As John Wesley believed, presbyters (elders, priests) could validly ordain other presbyters, though it is properly (licitly) done by a bishop (who himself is merely a presbyter entrusted with the authority to ordain). This was the justification John Wesley used to ‘set apart’ Thomas Coke and ordain other presbyters, as he did with Richard Whatcoat and Thomas Vasey for sacramental ministry outside of England. Wesley felt the extenuating circumstances justified ordaining in the presbyteral mode because (according to Wesley) it would be valid, but abnormal.4

Generally, at the consecration of a bishop in churches with episcopal polity, the rule of thumb is that at least two other bishops are needed for a licit consecration of another bishop, though technically a bishop has the power to illicitly consecrate another bishop with only one or no co-consecrators. The “rule of three” is not a conferral of validity, as stated one consecrator is technically valid, but it is a statement of the collegiality that comes with being a bishop. Bishops exist not as sole proprietors of a church—they exist in a college with all other bishops. The rule of three expresses the collegiate consent of the whole church to the new member joining the college. The rule of three is ancient and can be found in the canons of the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325.

Fortunately for the early REC, and those wanting to maintain a valid trail of episcopal apostolic succession, they began with a bishop! The founder of the REC, Bishop Cummins, was validly consecrated in the Protestant Episcopal Church, so any ordinations or consecrations he performed are valid. It was not long until Cummins solely consecrated Charles E. Cheney as a bishop soon after the REC was organized. This consecration is valid but illicit under canon law, as he lacked co-consecrators. Yet in two future ordinations, co-consecrators would appear who belonged not to the REC or another Anglican body, but bishops of the Methodist Episcopal Church.

William Rufus Nicholson

In 1876, William Rufus Nicholson was consecrated for the work of bishop in the REC. His consecrators are listed as Cummins, Cheney, and “Rev. Dr. Hatfield of the Methodist Episcopal Church.”5 The 1876 Journal of the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church lists a Robert M. Hatfield as the bishop of Philadelphia.6 This makes perfect sense as the REC was organized in Philadelphia, it was the site of several of its initial General Conventions, and supporting evangelical parishes who joined the REC were in Pennsylvania. It’s impossible based on the limited information we have to tell if Bishop Hatfield was friends with Cummins, Cheney, or Nicholson, supported the REC, or what prompted him to act as a co-consecrator. But he did, and Nicholson’s connection to Methodism is also as long and involved as Cummins.

According to his obituary, Nicholson converted to the faith as a result of a local Methodist camp meeting. He attended Lagrange College, a Methodist institution, and was ordained in the Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1847, he was ordained in the Protestant Episcopal Church, first as a deacon and three months later as a presbyter.7 In his writings, especially Reasons Why I Became A Reformed Episcopalian, we find much of the same evangelical attitude as Cummins, complete with ecumenical praise for Methodists:

[Reformed Episcopalians] are a body of Christians loving a liturgical form, yet, by no means repressing extemporaneous prayer. We prize our own green pastures and still waters; but often through the boundless landscape would we walk together with our Presbyterian brethren, and Methodist, and Baptist, and all who love the Lord Jesus Christ. It is, indeed, a goodly heritage.8

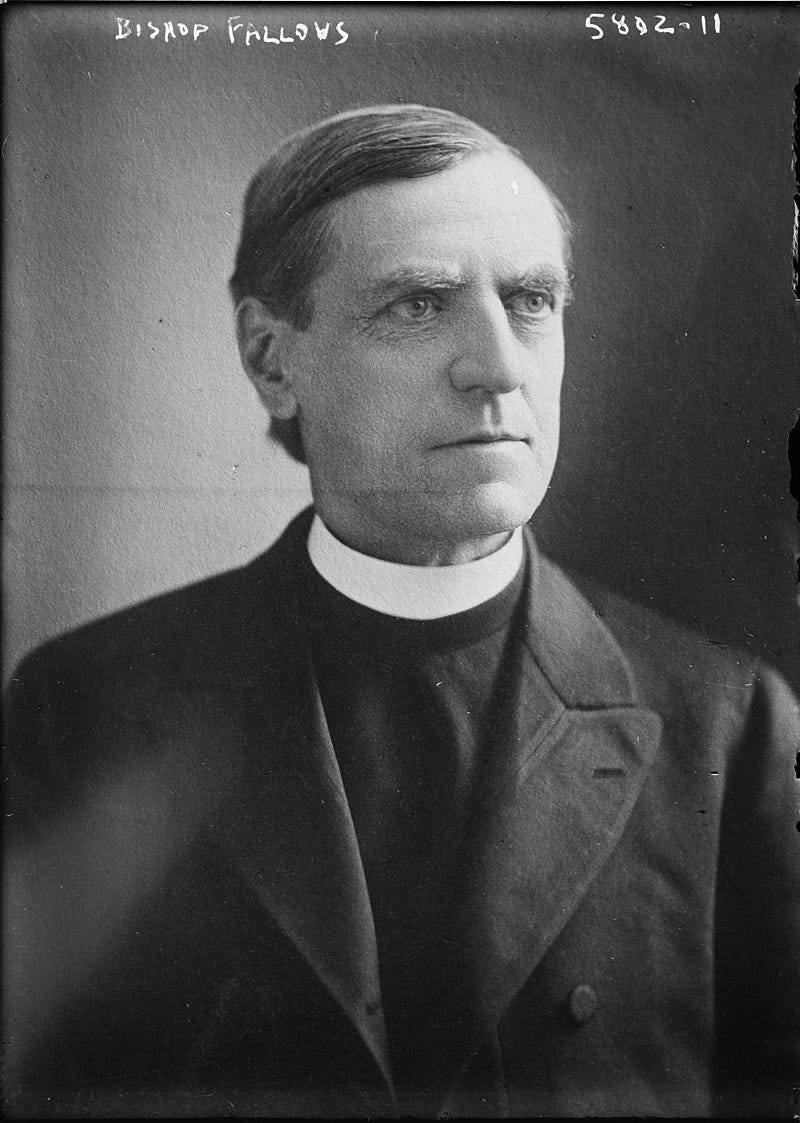

Samuel Fallows

In the wake of the death of Bishop Cummins, Samuel Fallows was elected and consecrated as bishop, and he is the most interesting of the men we’ll examine. His consecrators are listed as Cheney, Nicholson, and Bishop Albert Carman of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada. Interestingly, there are also presbyters listed as co-consecrators from a variety of denominations including the Wesleyan Methodist Church (now known as the Wesleyan Church).

Samuel Fallows was a very successful Methodist minister in Wisconsin, a decorated Army chaplain in the Civil War (attaining the rank of brigadier general), a superintendent of Wisconsin public education, and was the president of Illinois Wesleyan University. He was also an immigrant, born and raised in a class meeting in what was called the Wesleyan Methodist Church (now the Methodist Church of Great Britain). When he came to America his family turned to pioneering, and they attended camp meetings. After graduating college and experiencing the New Birth, he was given a license to preach. Fallows was a Methodist’s Methodist.

He was a zealous chaplain in the war, seeing the action as a holy war. Yet the war had a profound impact on him, and he struggled with doubt, depression, and despair. His commanding officer desired the Episcopal liturgy read, so eighteen prayer books were given to Samuel for use in the course of his chaplaincy duties. Despite the appeal of the prayer book, he asked his wife to help him ensure he didn’t become Episcopalian on its account. “I love liberty of conscience and opinion too much,” he said, “ever to cut loose from the Catholic Methodist Church.” He would return home from chaplaincy sick, but after he recovered he helped raise a regiment, and in 1865 raised a second, serving as a Colonel.

Fallows continued his ministerial service after the war, becoming the most prominent and sought after preacher in Wisconsin, serving faithfully at the two most influential Methodist parishes in the conference. Then he turned his talents toward education, serving the state schools as superintendent, where he made great strides in establishing and funding secondary education across the state. It was in this role he began toying with the idea of joining a church in the prayer book tradition. This journey culminated in a prophetic vision, described as follows:

Turning the question over and over, on a trip to a remote Teachers' Institute, in the jolting train murky with kerosene fumes, he had a vision that seemed to open heaven. He saw a new Church with the old, beautiful Liturgy, a Church opening its pulpit to other ministers, bidding all Christians to its communion rail. He beheld it Episcopal and evangelical, stately but loving, combining the virtues of Episcopalians and Methodists, omitting the faults of each. He even saw its name! The Reformed Episcopal Church.

When the REC formed a short time later under Cummins, Fallows concluded this could only be the same church in which he has seen in his vision—complete with the exact same name he saw. Ironically, as the REC formed, Samuel was offered ordination in the Protestant Episcopal Church by his wife’s uncle, a bishop. He saw a clear fork in the road but instead took a third option, becoming President of Illinois Wesleyan University. Soon after, he politely declined the offer by the bishop and connected with the aforementioned Charles E. Cheney, both dreaming of a mighty University of the West that would revolutionize education sponsored by the REC. He kept this decision to himself and continued to serve as president of IWU, pioneering the idea of granting degrees to Methodist ministers in absentia as they studied at home, essentially creating the first hybrid ministerial education program in existence. After turning IWU into an educational and financial success, he resigned and accepted rectorship of St. Paul’s REC in Chicago. This was not a decision taken without the counsel of his wife, Lucy, whom he had already argued out of Unitarianism and into Methodism before they wed.

"It's the Apostolic Succession," said Lucy Fallows, torn by all those discussions with her [Unitarian] mother. “Has the Reformed Episcopal Church that Popish thing?” This was no girl of eighteen he had to convince, but a woman grown, with strong opinions. She had pulled away from her beliefs once for love. So much the harder was the second yielding.

“Yes, my dear,” her husband said. “l think the Apostolic Succession is ours. But its significance to us is as a very beautiful historic rite. It is not mystic.”

In the next half hour, he was able to persuade her that the devil and all his works had been driven out of the new Church. He made her see that there was no Popery in its service or in its gowns and that the Christ of the carpenter bench was as truly in its midst as in the Methodist Church.

The Fallows’ clearly saw in the REC a continuation of their Methodist heritage, but with new and exciting opportunities to reach different people, minster as if all Christians belong to the Church regardless of denomination, and seek real social change. Ministering in Chicago, Samuel befriended Dwight L. Moody and ministered alongside him. He was one of only three Chicago ministers to support the school board when it dropped Bible reading and the Lord’s Prayer from the curriculum. He mourned the loss of Christian education, but thought in a progressive city like Chicago, with a significant Jewish population, it was the only way forward. He and his wife were active participants in the temperance movement, brewing their own “Bishop’s Beer,” which contained little alcohol.

It was this man, a man of vision and change, who was elected a missionary bishop at the death of Cummins. He traveled the nation and the world. He called his great evangelistic project “the Crusade.” He is reported to have had a significant ministry ministering to the black population in South Carolina. Later, as Presiding Bishop, he traveled to England, preaching in the Wesleyan Methodist chapel where he first testified to his faith in Christ, holding up the book of Wesley’s hymns his teacher had given him as a boy. He was invited to hold an audience with the Archbishop of Canterbury. He administered the Lord’s Supper in a joint service alongside Charles Spurgeon. Returning to the States, he found himself the unofficial chaplain of the Grand Army Reunions, standing next to General Sherman. He chaired several committees at the Chicago World’s Fair. He happened to be passing through and ministered to the steelworkers at the Homestead Steel Strike of 1892. He was elected to preside over the relief committee for the violent 1902 Anthracite Coal Strike. Wearing a combination of his bishop’s clericals and his general’s uniform, he managed to command the respect of every Catholic and/or military veteran, coal miner and capitalist alike.

Not only does he embody the great missionary zeal of seeing the world as his parish like Wesley, and offered a more conservative and evangelistic take on the late 19th century and early 20th century Social Gospel, but somehow he seemed to be everywhere. Appropriately, his biography is titled Everybody’s Bishop.9 An epic globe-spanning biopic on the level of Forrest Gump seems to be in order for Bishop Samuel Fallows.

Coming Home

Methodism in the 19th and 20th centuries was undeniably America’s religion. Perhaps more than any other tradition, it shaped the social, moral, and cultural fabric of our nation. In examining three out of the first four bishops of the REC, we can see an undertold story of that influence that deserves to be reexamined. The lives of Bishops Cummins, Nicholson, and Fallows exude the zeal and piety of the Wesley brothers, Francis Asbury, and Thomas Coke. I would argue they are heirs of that same movement.

It has been said the Mother-Daughter relationship of Anglicanism and Methodism is unique among churches. The trail from Methodism back to Anglicanism has existed as long as Methodism itself, and many have walked it. The peculiar part about this trail in particular that isn't present in probably any other tradition, is that one does not necessarily shed their Methodism when encountering Anglicanism. Rather they can willingly bring the evangelical zeal of Original Methodism to Anglicanism with them, where it first began in a small room at Oxford University with serious men—Calvinist and Arminian, low-church and high-church alike—asking each other the same question Thomas Cranmer asked: “How can we love God more than sinning?”

https://northamanglican.com/the-reformed-episcopal-church-and-her-detractors/

https://www.episcopalchurch.org/glossary/reformed-episcopal-church/

The reporting of Bishop Cummins life in this section is completely reliant on the memoir penned by his wife; Alexandrine Macomb Cummins, Memoir of George David Cummins, D.D. First Bishop of The Reformed Episcopal Church, By His Wife, (Dodd, 1878).

https://firebrandmag.com/articles/the-wesleyan-doctrine-of-apostolic-succession

Annie Darling Price, A History of the Formation and Growth of the Reformed Episcopal Church, 1873-1902, (Armstrong, 1902), 164.

Journal of the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, held in Baltimore, MD., May 1-31, 1876, (Nelson & Phillips, 1876), 46.

https://www.nytimes.com/1901/06/08/archives/bishop-william-rufus-nicholson.html

William R. Nicholson, Reasons Why I Became A Reformed Episcopalian, (Moore, 1875), 23.

Alice Katharine Fallows, Everybody's Bishop: Being the Life and Times of the Right Reverend Samuel Fallows, D.D., (J.H. Sears & Company, 1927).

Very interesting. It pleases me to know more of Methodism history. Difference of opinions is historical and I am now comfortable being in a UMC, although I strongly disagree with their politics. Our tithes go to the local church to operate and donate directly to worthy organizations and not to the region UMC hierarchy. I'm tired of seeking the "perfect" church. That does not exist, but love for Jesus and His word are what I follow. God bless.