Moving Beyond the Wesleyan Quadrilateral

A Proposal for Canonical Theism

I come from a long line of mainline Methodists through my mother’s family, so from an early age, I was taught the unique emphases John Wesley put on the Christian faith. As many have noted before, Wesley’s evangelism was instrumental in contributing to the Great Awakening and reshaping Christianity over the last 300 years. I began to develop a love for philosophy in my late teens and early 20s, particularly a field known as epistemology, which is the study of knowledge or, more specifically, what it means to know things. I was interested in exploring the ways in which Christians justify our beliefs as a genuine form of knowledge and, as a good Wesleyan, that led to my first introduction to the Wesleyan Quadrilateral.

The Wesleyan Quadrilateral is, as described in the Free Methodist Church’s Pastors and Church Leaders Manual, “an effort to describe a Methodist methodology for theological formulation.” In other words, it’s meant to be a way for Wesleyans to determine spiritual truth. And, in most of the Wesleyan circles I’ve frequented, it’s presented as *the* way to determine spiritual truth.

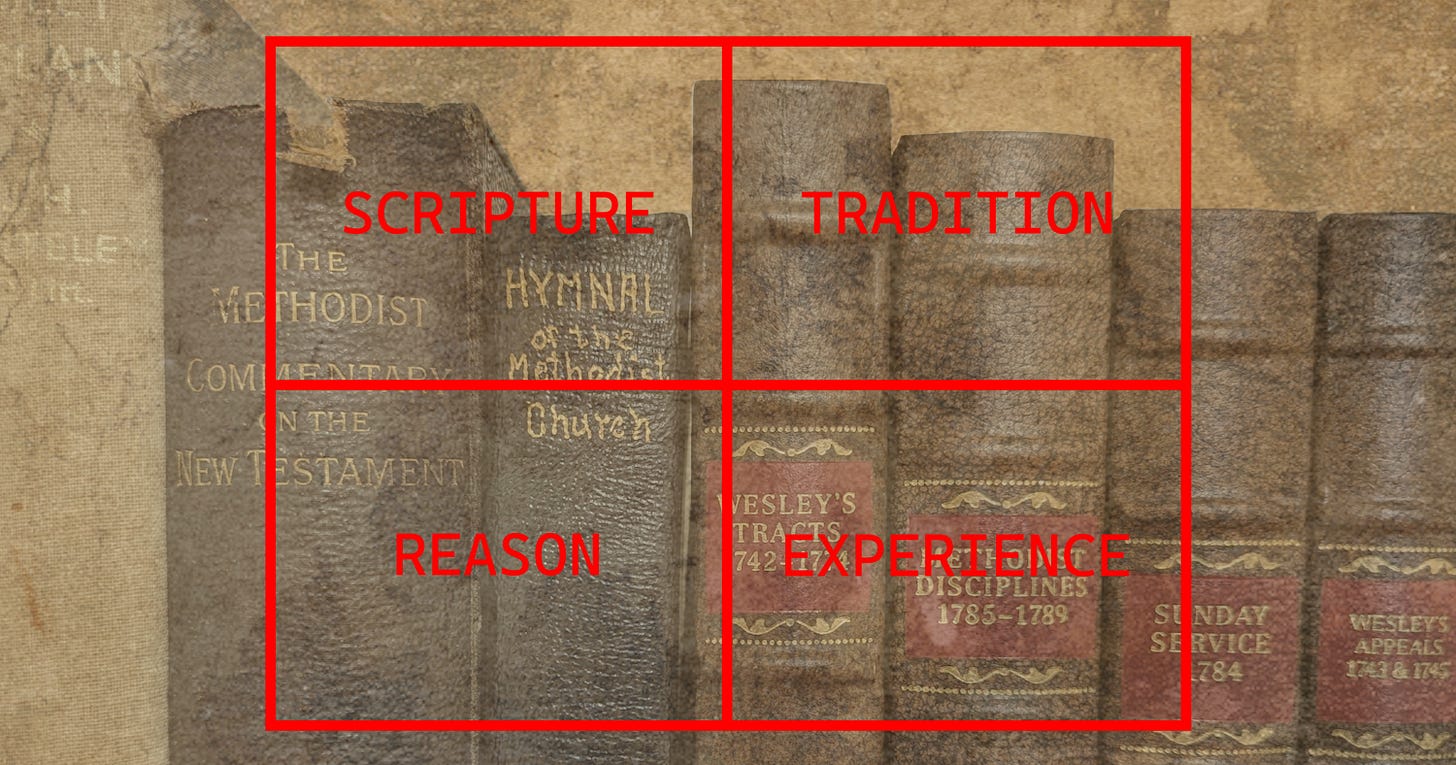

Theologian Albert Outler coined the phrase in the 1960s as his way of explaining how Wesley came to his theological decisions. It lists four sources of truth: Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience. The four are not supposed to be equal: Scripture is intended to be first and foremost, with the other three supporting it.

I’ve always felt a little uneasy about the Quadrilateral. It seemed that it tried to make something that is very complicated and messy – how we determine truth – fit into neat little categories. My qualms intensified as I saw my fellow United Methodists torturing the logic of the categories to turn personal beliefs into spiritual truth – Scripture was no longer treated as primary, and experience came to mean general life experience instead of the spiritual experience Outler intended. Thus, I encountered several Methodists justifying their theological opinions through the use of the Quadrilateral by claiming they’d witnessed particular things in life that made sense to them – never mind what Scripture and tradition had to say on the subject.

It was in the midst of my uneasiness that I came across the work of orthodox theologian and philosopher William J. Abraham, one of Outler’s successors at Southern Methodist University. As a theologian of epistemology and a Wesleyan scholar, Abraham piqued my interest with his critique of the Quadrilateral. Abraham traced the roots of the Quadrilateral not to Wesley but rather to Outler himself. Abraham, although a former colleague and an admirer of Outler, nonetheless bluntly said “Outler’s Wesley was an invented Wesley” in his 2005 article “The End of Wesleyan Theology.”

The Quadrilateral was born in the 1960s in the age of ecumenism that resulted in the formation of the UMC in 1968. According to Abraham within the same article, the Quadrilateral was intended by Outler as “a way to legitimize Methodism as a player on the world ecumenical stage” and as a way to help unify Methodists ahead of the merger of denominations that formed the UMC.

Abraham believed the Quadrilateral reflected both a bad historical understanding of Wesley and a bad epistemology of theology. According to Abraham, there was no other theological warrant for Wesley other than Scripture alone. “Wesley at his core was a staunch Protestant biblicist,” he wrote. “Drawing on a medieval vision of divine revelation, he was convinced that all proper theology had to be grounded in Scripture. Whatever bells and whistles we want to add either epistemologically or hermeneutically to this thesis, the ultimate test of truth in theology for Wesley was Scripture.”

Regarding the epistemology of the Quadrilateral, Abraham lists nine objections in his book Waking from Doctrinal Amnesia that he repeats in “The End of Wesleyan Theology.” Primary among those include the aforementioned misreading of the historical Wesley; the critical omission of special revelation as a means of knowledge; and, hinting at Abraham’s recommendation for a replacement for the Quadrilateral, “it provides for quick and easy proofs of critical Christian doctrine,” using the Trinity as an example, which is “easily proved…given its secure place in the tradition of the Church. If it is contained in tradition, then it is contained in a combination of Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience.”

A summary of the heart of Abraham’s critique is threefold:

The Quadrilateral is not a good representation of Wesley’s own theological process because, for Wesley, Scripture was the only arbiter of theological truth, despite the fact Wesley did indeed appeal at points to tradition, reason, and experience in his thought processes. This is Abraham’s point in stating “Whatever bells and whistles we want to add either epistemologically or hermeneutically to this theses, the ultimate test of truth in theology for Wesley was Scripture.” Otherwise, a person could associate basically anything after “Scripture” as something Wesley used as part of his thinking. Why not add emotion, for example, as Wesley seemed to be a very emotional person, so someone could make an argument that we should add that to the Quadrilateral since it surely would have impacted Wesley’s thought processes.

The Quadrilateral is not epistemologically or theologically sound. Theologically, it completely leaves out the category of “special revelation” as a means of acquiring theological knowledge. The Apostle Paul would likely have a bone to pick with that after his Damascus Road episode! Epistemologically, Abraham listed the following additional problems:

“It treats Scripture and tradition as epistemic concepts on a par with reason and [sic] experience, an obvious category mistake.

“When push comes to shove, as it inevitably will, reason and experience will be privileged over Scripture and tradition because the former are logically prior to the latter.”

“Epistemologically, it is severely underdeveloped, assuming that we know what to make of reason and experience.”

Perhaps the most important point that underscores all the others: Wesley was not a systematic theologian, and to try to systematize something of his that he himself never recommended others emulate is a massive category mistake. Wesley is our spiritual father and a saint, but he was not a John Calvin or a Thomas Aquinas or an Augustine as a theologian, and that’s OK – that isn’t a criticism. We need to emulate him in praxis such as in evangelism, disciple formation, and sanctification, but that doesn’t mean we should likewise seek to model our entire lives after every single aspect of his life (specifically here, his process of theological thought).

Canonical Theism as a Replacement

Using Abraham’s statement that “If [something] is contained in tradition, then it is contained in a combination of Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience” as a reference point, Abraham’s unique contribution to theology is a proposed new way of determining spiritual knowledge as described in his most robust book, Canon and Criterion in Christian Theology and the anthology Canonical Theism.

Canonical theism takes a broad view of the Church’s tradition. The Reformation emphasis on sola scriptura, or Scripture alone for Christian authority, was a needed correction for the Church in the 1500s, but one should step back and truly ponder the question, “What is Scripture and its history?”

Scripture is of course the collection of writings from the Old and New Testaments, but how were those writings selected? The answer is: they were selected by the Church. The Old Testament was essentially inherited from Judaism, but the New Testament books represent only a fraction of Christian writing from the era roughly extending from 40 – 100 AD, give or take a couple of decades.

Who chose which of those writings should be included as Scripture, which writings were authentic, and where to set a kind of “cut-off” date for the documents? Again, it was the Church.

Another way to label “decisions the Church has made” is the word “tradition.” So really, Scripture is best understood as a part of Church tradition. Making a distinction between “scripture” and “tradition” is a false dichotomy. Scripture is the written record the Church has decided is central to its tradition.

At this point, an additional question needs to be asked: “Why shouldn’t Scripture alone be sufficient for Christian authority as the Reformers claimed?” Simply put, we have the real-life evidence of thousands of Christian denominations to attest: because we can’t agree on how many parts of Scripture are best understood.

Yes, we can affirm Scripture is by itself sufficient to bring people to a saving knowledge of Christ, but there are many other issues left unaddressed by Scripture, and likewise, many issues within Scripture that Christians widely disagree on. What one Christian considers a “plain” reading of a portion of Scripture may indeed not be as plain as that Christian thinks.

As one classic example that resonates with Wesleyans, parts of Paul’s letters appear to “plainly” state women can’t lead in churches. Yet Wesleyan denominations rightly maintain that other parts of Paul’s letter provide a wider context in which to interpret those “plain” parts about women.

Put plainly (irony intended), there is less Scripture that can be understood plainly than we often like to think, as one might expect from a collection of books spanning about 2,000 years across multiple authors and cultures. The proof is in the array of Christian denominations forged by interpretational disagreement across hundreds of years. We need something more than our often-flawed individual ability to reason and our limited personal experience to make sense of our different interpretations of Scripture and the gaps left with issues not addressed by Scripture.

Canonical theism uses this logic as a starting point to launch into describing what aspects of shared Christian tradition, including Scripture, ought to be taken as definitive for a more robust, broader canon of authority. “Canonical theists call for a reevaluation of the standard scripture/tradition taxonomy,” writes Paul Gavrilyuk in Canonical Theism. “The canonical heritage of the church is constituted by materials, practices, and persons that formally or informally have been adopted by the whole church as canonical.”

Canonical theism considers the largely united theological consensus of the first thousand years of the Church as the authoritative heritage for all Christians. There were of course many sharp disagreements and heresies during those first thousand years (Arianism first among them) and one notable schism within the first five hundred years (Nestorianism), but through the first seven ecumenical councils, the vast majority of the Church was able to achieve consensus on matters of theology. It was only with the Great Schism in 1054 AD when the Eastern Orthodox Church separated from the Roman Catholic Church that divergent theologies began to rapidly increase.

Canonical theists list “eight components of the canonical heritage of the church,” according to Gavrilyuk:

Canons of faith (Confessional statements and creeds)

Canons of scripture (Lists of sacred writings)

Canons of liturgy (Guidelines for conducting worship services)

Canons of bishops (Approved lists of episcopal authorities)

Canons of saints (Lists of the saints venerated locally or universally)

Canons of fathers and doctors (Lists of authoritative theologians)

Canons of councils (Disciplinary and doctrinal guidelines imposed by the councils)

Canons of iconography and architecture (General rules regulating the depiction of God and the saints; rules of church architecture)

In short, these canons are inseparable from each other, because “scripture is a canon that developed alongside the canons of episcopacy, liturgy, and creed, interacting with them in a complex way,” wrote Gavrilyuk. “The canonical heritage, we argue, is a diamond with at least eight distinct facets, not a two-dimensional plane.”

A somewhat obvious critique of Canonical theism is that it doesn’t offer many clear-cut, definitive answers regarding what beliefs fall within the rubric of particular canons (the parameters of several canons appear somewhat vague), and I believe Abraham would agree. But I view this as a necessary reality – nothing in life is 100%, completely definitive this side of the eschaton, and to pretend otherwise is to be dangerously deluded. Yes, Scripture has authority and, yes, tradition has authority, but how they interplay with each other and mix with the authority of God divinely revealing truth to us is messy. If it weren’t, good Christians wouldn’t have so many disagreements because we could follow a rather clear chain of logic to arrive at the same or similar conclusions.

I think through Canonical theism, Abraham was trying to incorporate into Protestant consciousness a reality that our Roman Catholic and Orthodox brothers and sisters have recognized all along, and that is the uncomfortable truth that, in some ways, there isn’t all that much of a difference between the Bible and other forms of Christian tradition. Christians thrived for 300 years before the New Testament was officially organized, so (while they did have the Old Testament to rely on) it was, ultimately, the tradition of the apostles that guided their faith until the Church decided (via the Holy Spirit) to codify the New Testament as representative of – the exemplar of – that tradition.

The broader heritage outlined by canonical theism allows for a fuller and richer interpretation of scripture that assists in the understanding of its authority for Christians, and it helps in explaining how scripture is inseparable from tradition and what parts of tradition can be considered authoritative. While the Wesleyan Quadrilateral has elements of truth and was well-intentioned, perhaps it’s time we as Wesleyans accept that it has problematic historical and theological inaccuracies and look for a better way to explain how we determine knowledge and authority.

David S. Wisener is the pastor and church planter of Redeemer Free Methodist Church and is economic development manager for the city of Alachua, Florida. He is the author of the newly-published Lost the Plot: Finding Our Story in a Confusing World through Resource Publications. He has a BA in political science from the University of Florida and is pursuing an MA in ministry from Asbury Theological Seminary. He lives in Alachua with his teenage daughter, Naomi. More of his writing can be found at his blog, davidswisener.com.