Fourth Rome

A Commentary on Post-postmodernism and Conservatism

The City on a Hill

Shall this City, which is the hope and joy of all the Hellenes, the glory of the Eastern Empire, this splendid City, that flourished once like the rose of the field and was mistress of almost all peoples under the sun—shall it now be trampled on by blasphemers, and yoked in slavery? Shall our holy churches, where we have worshipped the Trinity, and sung the Liturgy, and celebrated the mystery of the Word made Flesh, be made shrines for the blasphemy of their driveling prophet Mohammed, stables for their horses and camels? Think of this, when you fight for our liberty.

The above quote is a fictionalized speech given by Constantine XI Palaiologos, the last Emperor of the Roman Empire, from Jill Paton Walsh’s fantastic young adult novel The Emperor’s Winding Sheet. Constantine was delivering the speech to his brave soldiers as they prepared for their last battle against the Turks who were about to storm Constantinople. Despite the legendary heroism of Constantine XI, the last-ditch efforts of Italian relief forces including the vaunted Giovanni Giustiniani, and the faith of the people, the city fell in the infamous siege of 1453.

The fall of Constantinople has been described by many historians as one of the great turning points in history. Oddly, it doesn’t get much attention today. What Walsh uniquely captures in her fictionalized account is something of the medieval mindset that we in the postmodern West fail to understand. The medieval mindset, aligned with almost every premodern mindset, understands that there are heavenly realities at play in everything. Right after Constantine delivers this inspiring speech, he rises from his throne and goes to each man in his company saying, “If ever I have wronged you, I pray you now, forgive me.” He begs this of everyone, then departs to the Hagia Sophia and attends the Divine Liturgy, names his sins publicly, and then receives absolution from the priest.

All of these actions are a requiem. Though the Emperor certainly intends to inspire hope in his seriously outnumbered defenders, everyone knows they are fighting a losing battle. The previous day there were numerous signs—supernatural and natural—that demonstrated, as Walsh puts it, “the Divine Presence was veiling its departure from the City.” One cannot miss the parallels between Jerusalem, of which Constantinople saw itself as a successor, and its Hagia Sophia as the continuation of the Temple. The fall of Constantinople has direct parallels to the fall of Jerusalem under Zedekiah. Like the Judahites, the people of Constantinople in 1453 believed God had abandoned them on account of their sins. Yet, Walsh fictionalizes Constantine saying in his great speech, “But if, because of my sins, God gives victory to the infidel, still let us face our ordeal in the true faith, bought with the blood of Christ.” Constantine, as thought of in the annals of Christian history, was no Zedekiah. He was a man of true faith.

The Third Rome

“I am afraid Heaven itself has turned against us.” - Constantine XI in The Emperor’s Winding Sheet

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453 an idea began spreading through Eastern Orthodox lands that Moscow was the “Third Rome.” Eventually, this theological concept turned into something of a legend before becoming a political policy of the Russian state as Ivan the Great took the title of Tsar (literally “Caesar”).

Despite the Russian dream of being a Third Rome persisting through much of the early modern period, Russia never liberated Constantinople (today called Istanbul) and this dream effectively died with the collapse of the Russian Empire and the rise of the atheist Soviet Union. The Soviet Union embraced atheism as the state religion, at times actively persecuting the Orthodox Church and other times doing their absolute best to ignore it.

Fast forward to today and the Soviet Union is no more. Orthodoxy, despite the persecution by state atheism, survived the Soviet period. There has been a resurgence of belief in God in Russia, but not without its qualifiers. Russia is a very different place than either Ivan the Great or Lenin envisaged it. Gone are the days of looking to Moscow as the great city of Christian resurgence, but also gone are the days of the fears of godless communism rolling over the green fields of Western Europe like a plague from the East.

On February 8th, 2024, American journalist Tucker Carlson interviewed Russian President Vladimir Putin. It was a very fascinating interview. No matter what your opinion of President Putin, Russia, or the current war in Ukraine is, it was a startling view into a possible future for what the West, particularly America, may look and sound like as we traverse the waters of postmodernism into whatever is next.

Postmodernism, or Post-postmodernism?

It is widely acknowledged that in the secular West, we live in a “postmodern” age, where faith and reason have departed the public square, and concepts such as objective truth and the soul are cast out in favor of relativism. Some have speculated that after postmodernism there is a “post-postmodernism” where faith or belief in God once again resurges but as a reluctant consort to reason, which is what is truly resurgent. Russia is unique in that it is far ahead of the rest of the West in its advancement through these ideas. Russia, under Soviet rule, already went through the Marxist reformations of dismissing truth, reason, the soul, and objectivity that we in the West are undergoing. It has come through this to the other side, becoming something else entirely. Russia, as Russian scholar Mikhail Epstein articulates it, has a phenomenon of “poor faith”. Essentially, after surviving atheism, faith did experience a resurgence as post-postmodernism contends—but thriving mostly in the bare minimum form of “belief in God,” devoid of the structures of religion.

“Atheism had used the diversity of religions to argue for the relativity of religion. Consequently, the demise of atheism signaled the return to the simplest, virtually empty, and infinite form of monotheism and monofideism. If God is one, then faith must be one.” - Mikhail Epstein

This doesn’t tell the whole story of course. Orthodoxy is still statistically the predominant religion in Russia, even if preyed on by these post-atheist cultural factors, and has a massive cultural influence on the nation. I have no doubt there are faithful Christians in many churches across Russia, but the perception is that the statistical rise of Orthodoxy in the post-Soviet era is largely a resurgence of cultural Christianity. Looking closer at Putin’s interview with Carlson, however, we can begin to see what a post-atheist nation may look like where resurgent “poor faith” makes bedfellows with a resurgent cultural religion. I believe it also points us to a reality American Christians need to be thinking about more deeply: what does an effective Christian political witness look like going forward? In America, Christians have historically had convenient allies in political conservatives, with Christians often filling the ranks of that group. This is an alliance that may be fraught with inconvenience in the decades to come if American post-postmodern political conservatism looks too much like the conservatism of Putin.

In the interview, Carlson endures a history lesson from Putin befitting any college history department (it was actually pretty good). This lecture portrays the sense that Putin operates with something of a medieval understanding of Europe. Several times, he noted the Orthodox culture of Russia and seemed to cite ethnic and religious concerns as though they were naturally part of national security policy. Take, for instance, his mention of Russian policy toward Serbia in the 1990s: “Russia could not help raising its voice in support of Serbs, because Serbs are also a special and close to us nation, with Orthodox culture and so on.” This may seem like a foreign idea to Americans, but this was once the prevailing idea in Europe, up until the middle of the 20th Century. Russia, historically, saw itself as the defender of Slavs and Orthodox Christians in Europe, a policy called Pan-Slavism. Look no further than Russia’s defense of Serbia in what would become World War I, which dragged the great imperial powers of the world into what could’ve been a regional dispute between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. This idea was hardly unique to Russia, with similar pan-ethnic movements all over Europe in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, leading to the creation of many nation-states we take for granted, such as Italy, Germany, and Greece. However, this view of pan-ethnic identity has largely been rendered obsolete in the late 20th and 21st centuries. France does not view itself as the protector of Francophone speakers in Quebec, Belgium, or Switzerland any more than Germany sees itself as the rightful ruler of Kaliningrad (which was East Prussia as recently as 1945).

It is fascinating that Putin would mention this idea so frequently. It is the opposite of the Marxist ideal the Soviet Union pursued, which encouraged relativism even in ethnic identity, which Putin mentions in the interview as it relates to the creation of Soviet Ukraine. He also cites it as a policy Russia is currently pursuing in Ukraine—the protection of those who identify as ethnic Russians. In this way, Putin demonstrates that it is possible to reclaim ideals and elements of a worldview of the past.

Orthodoxy?

Later in the interview, Carlson, an Episcopalian, takes the interview in a specifically religious direction. He asks, “You have described Russia itself, a couple of times as Orthodox – that is central to your understanding of Russia. What does that mean for you? You are a Christian leader by your own description. So what effect does that have on you?” Putin initially begins to answer as he has the whole interview, detailing some of the history of Russia becoming Orthodox. Then, the answer takes a radical turn: Putin, almost as if quoting Mikhail Epstein himself, begins to describe a trans-religiosity where Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism exist in a sculpture of harmony: “We are together, this is one big family. And our traditional values are very similar.”

To be clear, this is where Carlson asked Putin about his personal Christian faith. I do not think Putin was dodging the question or it was lost in translation. For Putin, the most important part of his personal faith is a plurality where every faith is united in its cohesiveness which holds together the Motherland. In other words, one’s personal faith matters very little, if at all. One can even have, as Epstein puts it, “poor faith.” What matters is that the faith a person has directs one to certain ends that align with the trajectory of the state. Religion is purely utilitarian.

Carlson, possibly thinking the question was misunderstood, asks a follow-up question: “So do you see the supernatural at work? As you look out across what’s happening in the world now, do you see God at work? Do you ever think to yourself: these are forces that are not human?” To which Putin replies “No, to be honest, I don't think so. My opinion is that the development of the world community is in accordance with the inherent laws, and those laws are what they are. It's always been this way in the history of mankind.” This answer is particularly shocking.

“For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places.” - Ephesians 6:12 (ESV)

In Putin’s answers, we can see the ideals of post-postmodernism at play. Reason is something he values highly, clearly appealing to historical reasoning, political reasoning, and even philosophical reasoning to make his arguments and deliver his lectures. Faith, or religion, however, clearly exists in subservience to reason, as a mere aid to it. Absolute truth is not needed, instead, as long as you can point to a fundamental truth—like a god is real—absolute truth claims like the Christian God is real are not needed or are secondary. If it were absolute truth that the Christian God is real, it would require contending with Divine intervention, which is not reasonable to Putin. Rather, laws are at play that have inertia and carry people, empires, and events to a certain end and only man has the power to intervene and rule over them. In this worldview, God is a nonfactor, not sovereign over nations. This is the reason that, despite relying on historical appeal at times, modern Russia has not returned to its birthright of being the Third Rome. This is a fundamentally different worldview.

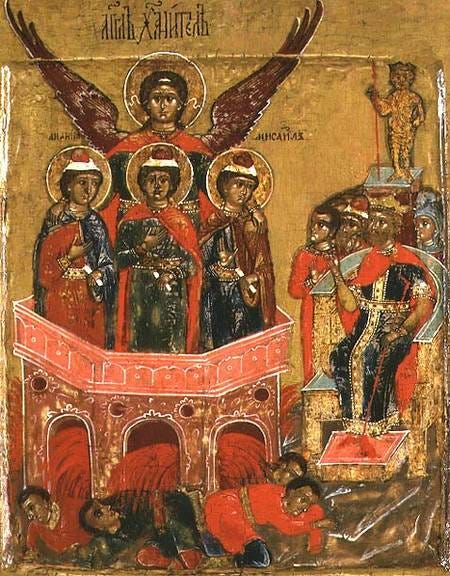

This brings us full circle to Constantine XI. People with a truly traditional and conservative worldview, founded in Scripture, see the Divine at play. Like Constantine looking up at the supernatural lights through the thick fog in the night sky as the Divine Presence leaving the City, and like the later Rus people, imagining the Presence has now turned to Moscow, so that they may one day liberate Constantinople, have a deeply rooted understanding that there is a heavenly realm. God is at work. Angels and demons are real. There is a cosmic battle at hand. In the end, the Kingdom of God will rule every corner of the Earth. Maybe we don’t understand everything, but we must “face our ordeal in the true faith”. This classic worldview is diametrically opposed to the supposed conservative worldview found in post-postmodernism. Only one of them can be truly traditional.

It is not hard to see that American conservatism is on a trajectory toward post-postmodernism. If carried to its natural end, it will cease to be an appropriate ally for Christians. Like the “conservatism” of Putin, which seems to be supportive of traditional values like the nuclear family, traditionalism, national identity, and traditional sexual ethics, the conservatism of post-postmodernism actively promotes another god—a pluralistic, absent clockmaker who has little-to-no divine agency and serves to support something rather than be the foundation for it. If god is a nonfactor in the inertia of nations, as Putin claims, then it must not be the Christian God who gives authorities their existence and institutes them (Romans 13:1).

Another clear evidence of this is the glaring reality of the Putin interview—the callous disregard for human life he demonstrated. Toward the beginning of the interview, amid the history lecture, Carlson asks, “Do you believe Hungary has a right to take back its land from Ukraine? And that other nations have a right to go back to their 1654 borders?” Putin gives a non-answer, ending with a “possibly.” Even if everything in Putin’s narrative is true, his war does not meet the minimum criteria for just war. The cost is currently in the tens of thousands of lives. If the attempted usurping of the true God was not enough to convince you, perhaps the negation of the imago Dei, the image of God in man, does. In this worldview, man does not exist to serve God, rather man exists to preserve the current order, the state, and its values—or die trying. When an ideology gets to that point, what are you even fighting to conserve?

I am not the arbiter of the future. I can’t pretend to be able to prophetically understand geopolitics, much less the future of internal American politics. That’s way above my pay grade. It’s entirely possible America doesn’t experience a fall into post-postmodernism like Russia. Maybe prudent allies Christians must make and everything will turn out fine. But at the end of the day, we must know whom we will serve. Christ is Lord of all.